Gallerie

A Larger Purpose

Jana Rogers' Creative Responsibility

This article first appeared in The Ski Journal Issue 15.3

CROUCHED on a ridge in Austria’s Zillertal Alps, photographer Jana Rogers observed the fading light in the snowcapped peaks The clouds had shifted allowing the sun to illuminate the rocky ridge above the slope, a photographer’s dream. The skiers dropped in and arced a few perfect turns down the untouched pitch. It was 2018 and Rogers felt an overwhelming sense of peace, living a career she’d so artfully crafted for herself. Only a few years after throwing herself into the world of ski photography, she was packing her schedule with trips to Europe and Japan, working big commercial shoots, like this day in Zillertal, all over the world. Still, she couldn’t shake a lingering guilt. “I felt so much gratitude and joy, but I also felt this pang of uncomfortable hypocrisy,” she says looking back on that winter. “I asked myself, ‘What am I actually doing to give back and protect these places?’”

ABOVE After my first Krampus–a raucous pagan ritual to disperse winter’s ghosts in Austria to nearby Bavaria–we awoke to three feet of snowin a ghost town. I was staying in a little farmhouse in Lech, Austria, thatsmelled of liver stew and homemade candles, and skiing every day.

MOST OF ROGERS’ childhood memories involve trails, beaches or snow. Exploring tide pools on the Oregon coast. Wandering through the Tetons every school break. Her mom, Janet, was a biologist working as a naturalist for Grand Teton National Park. From the time Rogers was 2 years old she spent summers in her mother’s footsteps, learning about the land and how to take care of it. Living inside the park at the Teton Climber’s Ranch, Rogers was surrounded by park rangers, wildlife photographers and climbers, a community that had dedicated their lives to the surrounding wild spaces.

“I was really captivated by these people who worked hard to spend time up in the mountains and were able to do so in a creative, artistic way,” Rogers says. “That was when I first learned to sit still in one place and just be. There’s such a deep connection between being in the mountains and creating something while you’re out there.”

ABOVE Snow came early to Alaska, blanketing the Kenai Peninsula. Depleted food sources pull the bears closer this time of year as they prepare for hibernation. I sat alone and watched as these two grizzlies shared a gentle moment. Mountains have exposed meto wildlife’s harsh realities. Photography helps tell the animals’ stories, inspire thoughtful coexistence and highlight the threats they face in a shifting world.

Rogers’ grandfather is also a biologist, and lives on a farm in New Hampshire, a land easement that has been in the family for nine generations. When she visited in the summers, he insisted that everyone in the family be working in some way to care for and protect the land, whether it was removing invasive species or starting an osprey nesting program. It was there that Rogers started to see the world through the lens of conservation, her grandfather instilling the idea of protecting the land you love.

Winters, on the other hand, were spent at home in Gleneden Beach, OR, skiing at Mount Hood every chance she could get.

“My family had two rules,” she says. “One: You can’t say you’re cold, and two: When your jacket is soaked, grab a dry replacement from the car and keep skiing until the last chair.”

ABOVE High in Austria’s Zillertal Alps, we hunkered in the dimly lit bar. After the last schnapps was empty, the conversation shifted to the angle of the roof. With a warm laugh, and no concern for liability, the bar owner pulled open the staircase to the roof and gestured upward. Amie Engerbretson and I stood watch, and in the last light I caught this shot of Mark Morris exiting the bar to a broken rib.

Rogers studied design with an emphasis on sustainable products and materials at the University of Oregon. But after graduation, she couldn’t bring herself to take the job she had lined up at a big firm. “I remember calling my dad in a panic and he said, ‘Well if you could do anything, what would you do?’” she says. “Immediately I thought to myself, I would ski.”

So she started a small design studio in Bend, OR, and chased snow. She worked from the road, skied almost every day, took meetings from the chairlift and scoured base lodges for free wifi. She coached Mount Bachelor’s freeride team, got her PSIA III certification, and started touring more. The recent college grad discovered she felt most at home in the backcountry, which offered her the chance to connect her love for skiing with the wild places she’d grown up exploring. Rogers gradually set her sights on bigger objectives, feeling stronger each year, until a spring 2016 trip to Valdez, AK, changed everything.

Her party of four was pitching out a long, exposed Chugach run known as the Hammer. Rogers and two of her partners were perched on what they had all agreed was a safe zone when a massive avalanche ripped out above them, propagating farther than any of them had anticipated. With only a split second to react, Rogers made eye contact with her friend next to her before the weight of a freight train pulled them off the mountain. “Everything got really dark and I was just getting rag-dolled down the mountain. I was sure I was going to die,” she says.

After getting pushed thousands of feet and flying over a rocky cliff band, Rogers miraculously stopped moving with her airways clear—alive but with spinal damage that would keep her away from skiing for the next year.

ABOVE A charge runs though Chamonix, where the black crows fly. Peering down this solid granite spire, there are endless icy couloirs and surrounding peaks. A friend set me up with photo work, and I arrived in Chamonix for the first time at the height of the climbing season. The magnitude was exhilarating, challenging and fast-paced. While descending I tucked into a high hut late into the night, finishing the dark miles to the valley under moonlight.

After months of physical therapy, Rogers moved to Utah’s Wasatch Range and cautiously approached the mountains again through a different lens—both literally and figuratively. “There was a lot of trauma I had to deal with after the accident and I eased back into skiing really slowly, so I just spent a lot more time shooting,” she says. “It became this grounding force, like a meditative art. It slowed me down, helped me notice things I hadn’t seen before, and really pulled me into the moment.”

The Wasatch is home to some of skiing’s top photographers, and Rogers got to learn from pros such as Adam Barker, Lee Cohen, and Will Wissman. “All those guys were really encouraging,” she says. “Adam was really supportive of getting more women psyched on photography, and he was always there to answer questions when I had them.” Barker, who was born and raised in the Wasatch, recalls Rogers’ maturation as a photographer, “It’s as if all the dots are being connected. Tack sharp, well-composed, accurately exposed—her work looks polished. You can tell she’s worked hard in honing her skills.”

Rogers’ journey has taken its own unique turn, however, one facilitated by her fascination with the sheer magnitude of the natural world. Today her eye searches for contrast, for light and the movement of shadows across the mountains. Shots of tiny humans etching paper-thin turns into untouched slopes focus more on the mountains themselves. The humans, on the other hand, become secondary. It didn’t take long for her work to get noticed, leading to commercial projects with Icelantic and Spyder. Soon she was travelling Europe; Zermatt one week, Engelberg the next.

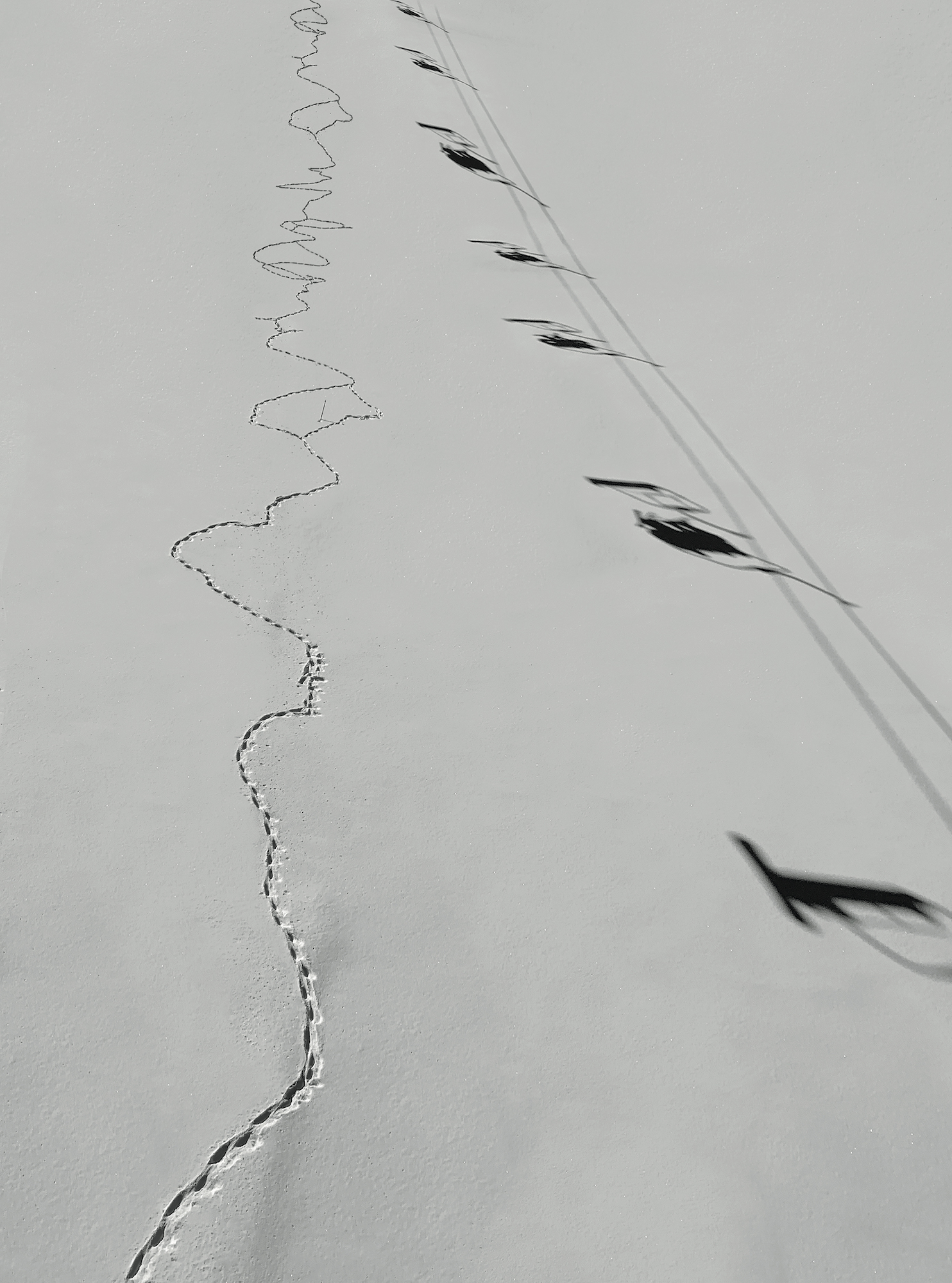

ABOVE Winter is our playground, but it’s also a critical time of survival for the wildlife that call the mountains home. A reminder of the tension between recreationalists and the true locals, as paw prints mimic the shadow of the lift at Engelberg-Titlis in Switzerland.

But it was there, shooting dreamy powder photos in Zillertal for a ski catalog, that Rogers knew she needed to make a change. “I felt out of alignment. My work lacked a larger purpose,” she says. “Standing there, feeling that awe and connection of being in these mountains, I knew I had to realign to work in ways that foster conservation of places like this. We’re making money off these places, but what are we doing to conserve them?”

She thought back to those summers in the Tetons, of conservation projects on her grandfather’s farm. She thought about her grandfather’s words: “If you love a place, you have to do something to give back to it.”

ABOVE When I think of big air and backflips, I think of Owen Leeper. He is a true athlete, something you quickly learn on a boot pack, but my trust in his instincts is why I love skiing with him. This trip we hopped a train to Ski Lodge Engelberg after a storm, and this air overlooking the valley below opened up the day.

Alpine photography sits close to Rogers’ heart, a way to blend her childhood roots in natural spaces and her love for skiing and action sports. She’s one of few people who get to weave these landscapes into her everyday life, and her lens has given her a unique look into these environments. But as remote and wild spaces see more and more traffic in summer and winter, the fast pace of ski and outdoor photography doesn’t always keep up with the growing impact that humans have on these delicate environments. “Recreation in itself is not a conservation act,” she says. “We want access. We want to use public land. We want to pursue sports that enrich our lives. We want to travel and see new places. We want to share the imagery and build careers. But the question becomes how is big rec, and those of us that promote it, participating in conservation?”

She knows that film crews are often big, and the high stress of nailing deliverables in a short period of time can leave things like carrying out waste as a lesser concern. As she came to terms with the environmental impact of her profession, Rogers had a realization: “The best shot isn’t always the most responsible one.”

ABOVE When you dive under a wave there is a second when you are totally present. This exists in skiing as well, that suspended meditation of movement. On a sunny day in the Uri Alps of Switzerland, Owen Leeper pulls out of an overhead Swiss barrel.

Instead of focusing on the doom and gloom of overcrowding in the backcountry, Rogers saw opportunity in photography. When used properly, a camera is a powerful tool to stir up change, a chance to educate.

She took a step back, reevaluated, and sought out brands and partners working to protect the land and use visuals as a way to encourage proper land stewardship. Through a mutual friend, Rogers connected with world-renowned Canadian conservation photographer Paul Nicklen, whose work combining photos and environmental narratives had a dramatic impact on her. Rogers worked with Nicklen on his branding, and saw the power and depth imagery could create in protecting the world around her. He showed her that wild spaces and wildlife depend on education and action, something that resonated deeply with her as she sought out future projects.

ABOVE Perched near a cornice in the Grand Targhee backcountry of Wyoming, I awaited the radio countdown from Julian Carr. The air felt electric in the weighted stillness of anticipation. Drops like this require time and precision, everything has to line up. Suspense, movement and then weightlessness. In this frame I saw the cornice snap, and the debris overtook Julian. I reached my exit point just as Owen Leeper confirmed all was safe from the opposing ridgeline.

ON A COLD HOKKAIDO skintrack, things seemed to fall into place. Rogers and professional snowboarder Rafael Pease started chatting about endangered species in his home country of Chile and when he invited her to join his next project with Chilean production, Connections Movement, she jumped at the chance. The film project, Tupungato, follows Pease’s human-powered winter expedition on Volcán Tupungato, a 21,555-foot volcano along the border of Chile and Argentina. It aims to bring awareness to the efforts to create Chile’s Tupungato National Park, a significant source of freshwater with over 140,000 hectares of mountains and glaciers outside of Santiago. “If you’re gaining attention or popularity from photography in wild places or of wildlife, then I think that’s an invitation to step forward into conservation,” she says. “Especially since you’re literally building a career off of something that might not always exist unless we’re really vocal.”

ABOVE In the blur of many sleepless nights, we watched the fire fox move across an ink black sky. The thin threads that connect us all: life, breath, movement, curiosity. Every light display is as unique as a snowflake, and every culture has rich mythology tied to these mysterious events. Standing frozen on the fjord outside of Reykjavik, Iceland, this is the only time I thought I heard the elusive noises that rarely accompany the lights, like the faint rustling of silk.

These days, Rogers has traded the lively Wasatch hustle for a quieter life in northern Montana. She’s working to spread awareness about bills that threaten the local wolf population and pitching campaigns that promote Leave No Trace practices, highlight endangered species and provide examples of strong environmental stewardship from the perspective of a skier. The power of shared joy through ski photography continues to inspire her, but now she’s linking that with the narratives that have shaped her character, shooting photos of receding glaciers and the effects of increased traffic in well loved backcountry zones.

“I think the big question for me as a photographer moving forward is: What does creative responsibility look like and how can I use my photography and love for the mountains to elevate the environmental conversation?” she says. “For me, recreation without active stewardship lacks accountability.”