Interview

Rainer Hertrich’s Endless Winter

For eight years straight, Rainer Hertrich skied every day. Now the Copper resident faces new challenges in the wake of his historic run.

To ski every day for over eight years, Rainer Hertrich sacrificed a lot. He put aside relationships, and pushed through injuries. He even took midnight runs on travel days to make the flight from northern to southern hemisphere without missing a day on snow—anything necessary to arrange his life into a single endless winter.

During his world record ski day streak, he skied nearly one hundred million vertical feet. An emergency cardiologist appointment revealed a heart condition that abruptly ended that quest, but the adventure led to a book, “The Longest Run.”

A lot has happened since the streak ended in 2012. Rainer has returned to his love of long, solo motorcycle trips—another aspect of life he largely sacrificed while getting himself onto snow every single day. He also had his foot amputated, something he attributes to nerve damage suffered, in part, from jamming his appendage into ski boots over 2,900 days in a row. Though the loss of his foot forced him to abandon his long-time career and passion as a groomer and cat operator, he still managed to ski over 100 days the year following the amputation.

From his home in Copper Mountain, CO, Rainer is currently weathering the pandemic nursing a broken ankle that had already cut his ski season short. We caught up with him to talk about his streak, his unflinching motivation, and what he loves so much about the sport that’s led him to spend more time on skis than likely anyone else alive.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The Ski Journal: Looking back on your streak, what did you learn from it and how did it change you?

Rainer Hertrich: I wouldn’t say it changed me, but the streak made me commit. It made me resourceful. The first year, when Timberline (Oregon) closed on Labor Day and I knew there was nowhere in Colorado to ski until mid-October, I wasn’t sure what to do.

The Andes had always fascinated me, but now I had an excuse to go to South America. I picked out Valle Nevado, Chile; It was close to an airport, it was possible to get there without missing a day, and I was willing to roll the dice.

That first year was a big gamble with how I got to places. The next year I decided to not rely on public transportation and rent a car to give myself the option to go explore other areas. I met a lot of people who helped me out. I started to look forward to going down to South America every year. I got my confidence up, met more people, and that was just part of the reason for keeping it up.

I never thought that a heart problem would stop my streak. I figured a broken leg, busted hip, torqued knee, or something like that would stop it. I’d already skied through a couple of broken ribs. I crashed hard a few times, but I skied through it.

In your book, you talk a lot about enjoying a good challenge. Was it the challenge that made you want to keep your streak alive?

The challenge was a lot of it. The first year I wasn’t really going for a record. I didn’t really know about the previous world record.

A friend had turned me onto the Avocet watch where you can keep track of your vertical. I was skiing every day—that’s part of the groomer job—skiing around and seeing what needs to be addressed.

I was curious just how much I actually skied. I figured I’d hit a million feet, and I ended up skiing double that.

The next winter I went up to Jackson Hole and saw a plaque in the Mangy Moose with names of people who’d skied 6 million vertical feet in a season. That got me thinking. Copper has fast lifts. If I ski 33,000 [vertical feet] a day, I could do a million in a month. And we’re open six months. That year I made 4 million, and the next year I did 6 million, then 7 million.

The two promises I made to myself were that if I get really injured, I’m done. If I go broke, I’m done.

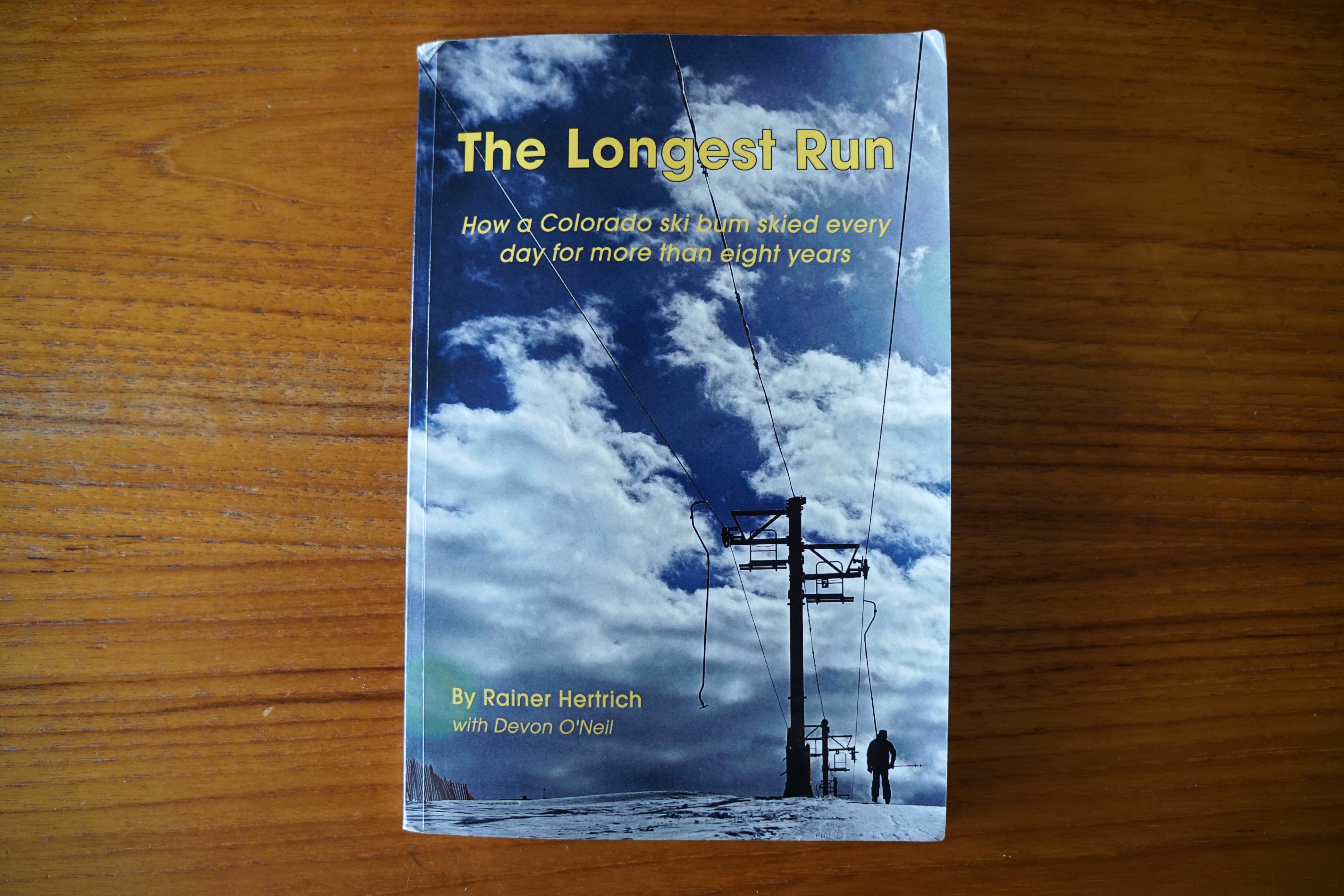

ABOVE Hertrich published his ski streak memoirs in 2015. Life has been interesting ever since.

You ended up breaking that previous record pretty early on in your streak. What was your motivation to keep it up for eight years?

I wanted to have a story to tell. I knew it was a story that people would want to hear. It’s a big story digging back 20 years. It’s deep, kind of like the powder should be around here right now.

But more than that it became about the numbers. 100 million vertical feet became a magic number for me. As I got more and more into counting my vertical numbers, I was like, “Can I make the text ten million? Can I make the next ten million?”

And when my streak ended I was so close to one hundred million [vertical feet], I was so bummed. Not to mention I only had a week to go to hit 3,000 days.

I did hit 100 million vertical that year. I don’t think anyone will ever ski 100 million vertical feet quicker than eight-and-a-half-years.

A lot has happened since the streak ended.

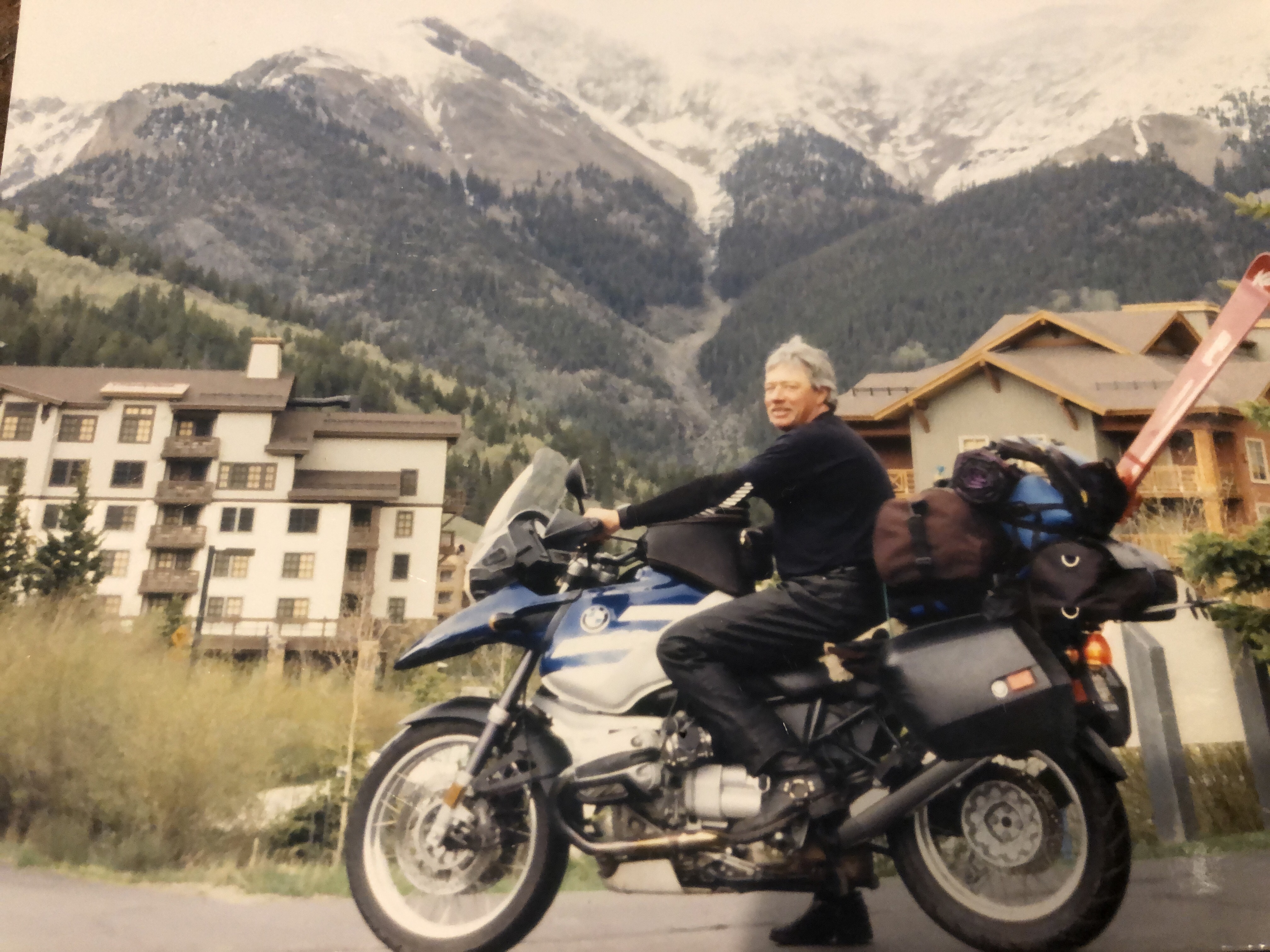

I kept on grooming at Copper in the winter and at Timberline on Mt. Hood in the summer. In the fall since I wasn’t going to South America anymore, I’d go touring on my motorcycle. I had a ski rack on the bike. I put in a lot of miles.

So that happened until I learned that I was going to lose my foot.

Can you talk about that?

I’d been in Hawaii and had what looked like a hiking blister on the bottom of my foot. I thought it wasn’t a big deal. I started trying to ride back to Alaska again because I hadn’t been there since before the streak. I’d been in my riding boots every day, and my little dry blister got worse and worse and bleeding. Then I started to feel creaky noises in my foot. I needed to get home and deal with it, so I turned around.

Turns out it’s called Charcot foot. They could have done surgery with cadaver bones, giving me a 50% chance of it working, but I’d have a club foot either way. By that point I’d been in severe pain for six months, so I said to just cut the damn thing off.

What was it like learning to ski again?

It’s been a challenge A challenge to me is an adventure. And I love adventure.

I started getting back out on skis sooner than the docs would have liked, but they knew me and knew that’s what I was going to do. Otherwise I’d have just been sitting inside. And that’s not who I am.

I started skiing on easy runs. I didn’t care about vertical anymore. It was more about spending time on the hill until it started to hurt. I’d do one run a day then work my way up to two. I was getting used to the pain and my skiing strength was gone. It was like starting over again and learning how to make turns again.

I just worked my way up so I could ski longer without getting tired. Then I’d do two, three, four hours a day. Or basically I’d ski until I was cold. When I was on the streak, cold didn’t matter. I skied 111 days that first year, and got stronger.

I try not to look at it as a disability. I try to look at it as a challenge, which helps me stay motivated. If you think of it as a disability, it’s a bummer.

ABOVE Hertrich spent years cruising from ski spot to ski spot on his motorcycle. Photo: Ginger Gamage

What is it that you love so much about skiing?

Over the years people kept asking me that. My answer was that it’s flat out fun and it’s the fastest you can go on your feet.

Also, the people you meet. It’s good to talk to people because you find out all kinds of cool shit. People are scattered all over the world. I’ve got friends everywhere.

I’ve met people who were poor but were happy, and they’d do whatever they could to help you out. And help doesn’t have to be money—a bed or a roof over your head is help.

Plus, I’ve gotten plenty of chairlift time to think about things and question things.

Chairlift rides are good for that. What would you say to the people who think that counting days and vertical feet goes against the purity of the sport?

I don’t think counting what you do is anything against the purity of it. Some people get one day a year and enjoy the shit out of it, and that’s what it’s all about, enjoying it.

There were days where I had to make myself get out there because it wasn’t that enjoyable. It was raining, or it was really hot and the slush was eight inches deep. There were days where it was breakable crust, or the snow that I call coral reef—where it was slush that never got groomed and had frozen solid. Nasty.

But then you get the days where it’s like, this is the best day that I’ve ever had. One day that sticks out in my mind was up at Timberline. I happened to be starting up the mountain, and the lift mechanics were heading up to the top of the Magic Mile, and they gave me a lift. It was raining, but I thought I might as well just keep hiking to spend some time on the hill. And it was solitude, totally quiet. The lifts were off. Nobody around.

That day they were hauling the rails out of the park. Every time they drove down they groomed it. They left tiller passes. And all of a sudden, the clouds broke, I was able to see Mt. Jefferson. I was in three layers of clouds, the sun was shining, and it was one of the most beautiful peaceful moments, such a pristine thing.

I made 220 turns to the bottom. I was counting each one.