Travel

The Safest Country on Earth

Fear and Confusion in North Korea

ABOVE The underground metro system in Pyongyang is the deepest in the world, and for a reason: It’s also designed to be used as an underground bunker in case of attack.

She is holding a microphone, big eyes staring straight into mine.

“Would you like to sing with me?” she asks.

I can’t say no, and as she leads me to a screen across the on-hill café I awkwardly try to retrieve my hand from hers to grasp the microphone. The music starts, and as the words fly across the screen I know I am utterly fucked.

The song is not just in Korean. The words on the karaoke machine are in Korean characters. Not wanting to offend, I try to replicate the sounds she is making. It rapidly disintegrates into a suicidal farce. Yet she somehow smiles her way through my awful screeches, and thanks me as the music dies away. Welcome to lunchtime entertainment while skiing in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK).

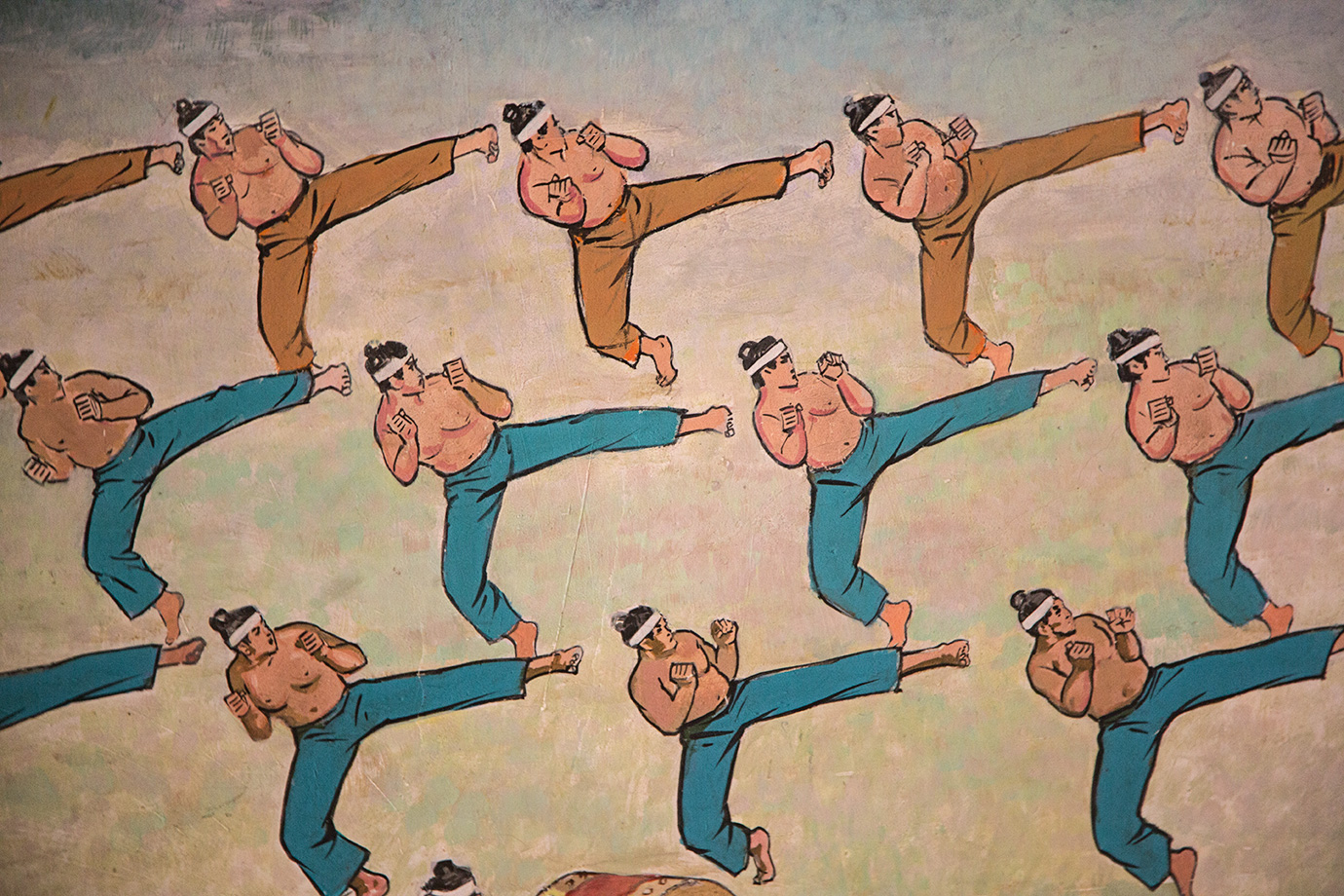

ABOVE With all the “new” of the Masikryong Resort and recently built parts of the city, it was interesting to see some of the “old” as well. Even though North and South Korea split in 1945, Korean culture—including martial arts—dates back millennia.

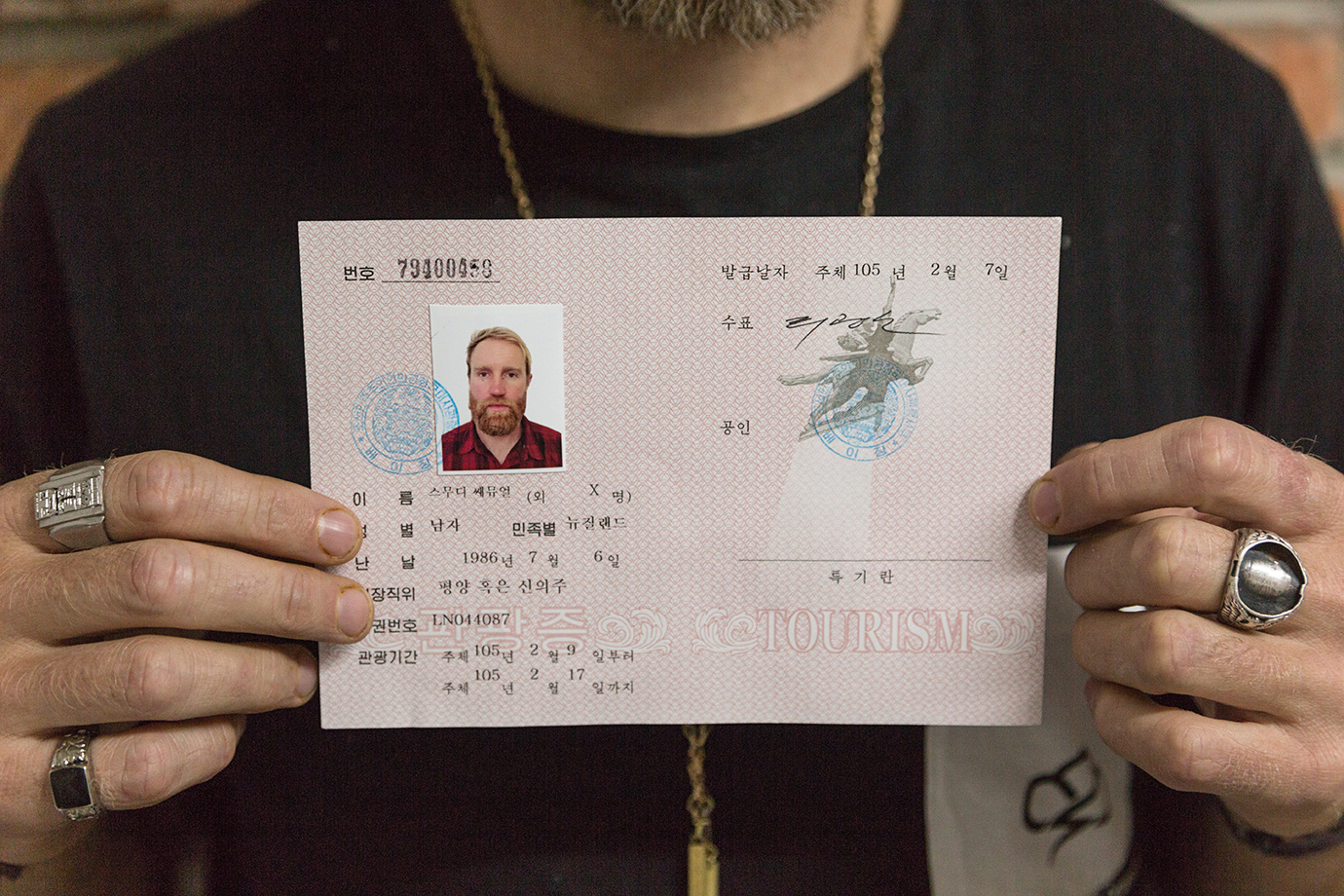

ABOVE While in Beijing, the DPRK consulate issued us temporary visas after taking our passports, to be returned when we left the DPRK. While unnerving, we did get them back. Unfortunately, we were not allowed to keep the visas.

ABOVE In Pyongyang, commercials and advertisements are replaced with propaganda, such as these billboards on one of the city’s main streets.

A few months before, safe at home in New Zealand, photographer Will Lascelles and I wandered the internet searching for strange, unlikely places to ski. Our attentions soon drifted to North Korea. The country’s only ski area, Masikryong, was opening for the first time to outsiders.

After contacting Koryo Tours, one of the few companies bringing tourists into the country, we had a rough plan of attack. But, days away from my flight, I heard a report of an American student sentenced to 15 years of hard labor in a North Korean camp, for removing a political banner from a hotel. I called Will.

“Hey mate, how’s the Freeride World Tour?” he asked. After I was silent for a moment, he continued, “Well, you called this late-night Skype meeting, so what’s up?”

“Will, are we going to come home from this trip?” I responded. “It seems I have grown somewhat fond of my life.”

Back in the present, standing awkwardly in front of the karaoke booth, I am even less sure of our upcoming fate. In some corner of my personality, I like skiing because it connects me to my internal fight-or-flight survival mechanism. And maybe my current situation is an extension of that—Exchanging the risk of avalanches for a potential internment camp.

—Sam Smoothy

Will Lascelles:

After hanging up with Sam, I sat at my desk, contemplating his anxiety. On top of the imprisoned student, Kim Jong-un had been shooting off even more rockets than usual, like a multi-megaton fireworks display. I had just assured Sam we were going to be fine. Internally, I wasn’t so poised. Seeing as we’d be meeting in the Bejing airport in a few days, that’s what he needed to hear.

The mood upon arrival in Bejing was a welcome distraction. It was the first night of Chinese New Year, and the consumer fireworks seemed tame as we watched the show over a few local beers. Booms and bangs popped off in all directions, a bit of crazy mixed with insanity—perfect for ignoring the dictatorial elephant in the room.

The next morning, we were scheduled to meet at the DPRK consulate before our flight, to get our visas and go through the do’s and don’ts of traveling to the Hermit Kingdom. Perhaps the beers weren’t such a good idea. The hangover, mixed with nervous anticipation, wasn’t the best for concentration.

Shortly after we met the Koryo Tour representative, a Scottish woman with purple hair who gave us “the talk”: A two-hour-long list of what not to do, with the cheery footnote that if we played by the rules, we would be in the safest country on earth. Apparently, people don’t break the rules in North Korea. Noted.

ABOVE To say we nailed the weather would be wrong. What we thought was going to be a saving-grace snow system turned out to be a balmy rain storm, leading to one of the soupiest ski sessions of our lives. Sam Smoothy navigates foggy trees at Masikryong Resort.

ABOVE To get from the capital to the mountains, we journeyed on one of the bumpier roads known to man. As it gained elevation, it passed through multiple tunnels, and roadside propaganda was plastered on every flat surface along the way.

Sam and I arrived at the airport early the next morning, shuffling to a check-in desk at the far end of an obscure terminal. The line was mostly North Korean nationals, with another tourist group playing the caboose. The loose gathering of a Norwegian, a Swiss national, two Aussies and an animated, Jimmy Buffett-esque American were also there to ski. And, like us, they were plenty nervous.

The “don’ts” started immediately after takeoff, as we were restrained from taking photos while in flight. It seemed unnecessary. The only thing below us was endless, frozen tundra. We put our cameras away immediately.

At customs, it seemed they already knew everything about us. Still, they gave our bags a vigorous inspection, opening our computers and asking to see our “Movies” folders. Before we left, I had deleted everything but GoPro shots. Sam, had cleverly moved his incriminating items to the trash folder. We passed.

Reewa was one of two guides—“minders” might be a better description—assigned to us for our tourism “pleasure and safety.” With a huge smile, she introduced us to our second guide, Chay, before we all piled into a van. The girls, both in their mid-20s and extremely friendly, were amused by the massive size of our ski bags.

As we drove toward the capital of Pyongyang, the girls began telling us eagerly about the accomplishments of the Republic, pointing to various buildings or monuments and explaining their significance. Most buildings are tall and boxy, covered in windows, and, from what Reewa and Chay told us, were built in record time. North Korean efficiency in action.

The history lesson made our arrival at the hotel even more glaringly American. Upon entering the bottom floor, a bowling alley was immediately apparent, and, upon further inspection, we found billiards, karaoke and pool tables—plenty to distract and entertain guests whose sole purpose was to not leave the premises.

We thought we would be scared, and we were. But the peculiar situation was also darkly hilarious. Here we were, two idiots adrift in a communist sea, put up in the biggest—and mainly empty—hotel in which either of us had ever stayed, while we drank beers comfortably in a slowly rotating penthouse restaurant. Outside the windows were the colorful night lights of Pyongyang, which we had both thought nonexistent and which may or may not have served any purpose beyond being glorified Christmas lights. We tried to remain as open-minded as possible, and yet in less than a day the DPRK had us stumped.

The next morning we began our tour of Pyongyang, and I soon found myself approaching two towering, bronze statues with a wreath I’d bought at the hotel. The duo depicted former supreme leaders Kim Il-Sung and Kim Jong-il. I timidly set my gift at the feet of the 100-foot-tall leaders before giving a curt bow and slinking away awkwardly. Surrounded by gun-toting soldiers, our jetlag, Reewa’s incredibly fast English and our general state of confusion brought about our first—and not so insignificant—mistake.

“Why is he called Little Kim Jong-il?” Sam asked. “It seems a bit unfair. He is little, but then most of you are a bit short, comparatively. And he’s not much smaller than the other guy.”

“Its LEADER Kim Jong-il, not LITTLE!” Reewa snapped. “You can’t call him little! He hates that!”

Fucksticks. Day one in the DPRK and I was seriously questioning my ability to not get myself shot. What are we doing here?

Our next stop was much more mundane: A four-story supermarket, where we were surprised by the mass of people buying beer and chips. The stacked shelves are the antithesis of what we had been told to expect. We had heard about empty stores, but this one was bustling.

How could this many shoppers be staged? An entire store? Surely this was impossible. Our reasoning fell apart as we attempted to get a handle on feasible scenarios. How could we know what was real and what was paranoia?

“The wide runs cascaded off the ridges, perfect for high-speed bombing or sending rollers into oblivion. It’s like the East Coast of the United States, just with kimchi instead of hotdogs.”

Skiing, we had known from the beginning, was to be almost a side note to the trip, and yet it was what had brought us here. And so, after a few days touring Pyongyang, we headed to the country’s only resort: Masikryong. Completed in 2013, the ski area rises nearly 2,000 vertical feet through the hardwood forests covering the area’s steep hillsides. A space-age-esque luxury hotel squats at the base, complete with a swimming pool, ice rink and multiple restaurants. The rooms even have internet.

As we loaded the area’s double chair, our guides set us free, with the caveat that we were expected home by lunch. At first it didn’t seem like a big deal, beyond the fact that it was the first time we’d been alone since arriving at the Beijing airport. Then we realized we could talk openly, saying whatever we pleased and going wherever we pleased (inside the rope lines, at least). Even in North Korea, mountains are free. Relatively.

Whether due to our atrocious Korean or inability to hold a precise edge while balanced on an inside ski, our efforts to join the local synchronised ski team did not go so well. Decked out in something akin to janitor’s uniforms, they followed each other down the mountain in tight formations of four or five, so coordinated they seemed to leave just one set of perfect tracks. Our butter 360s and side hits impressed them little, but everyone seemed to be having a good time.

Heading up the reasonably modern gondola—it was purchased from an Austrian ski resort and installed in 2015—felt like crossing an international border. The DPRK Ministry of Sports originally predicted an average of 5,000 daily visitors, and while skiers had plied the lower slopes, up here we were the only ones, roaming the silent pistes and snaking through trees eerily cloaked in clawing fog. The wide runs cascaded off the ridges, perfect for high-speed bombing or sending rollers into oblivion. It was like the East Coast of the United States, just with kimchi instead of hotdogs.

ABOVE While numerous groups of local skiers were on Masikryong’s lower slopes, all of which seemed to be enjoying themselves, the resort’s extensive infrastructure was eerily empty. It left us wondering, for who and what was all of this built?

Returning to the base area, we arrive at the aforementioned lunchtime karaoke debacle. With Sam having been thoroughly shamed, we continue our meal with heads down, waiting for our scheduled introduction to the head instructor. He has been skiing in the country for more than 30 years, beginning up north on Paektu Mountain—the spiritual birthplace of the modern DPRK. It was on Paektu Mountain where former supreme leader Kim Il-sung’s father is said to have been born, and developed the “Juche Idea,” North Korea’s founding philosophy of self-reliance and strength. We had hoped to ski Paektu Mountain, but are told snow blocking the road would make it impossible.

To ingratiate ourselves further with the ski resort hierarchy, we meet with the management and instructors. Things start off jovially, as we give them a few pointers on ways to improve the resort and tell them how much we enjoyed seeing all the skiers on the slopes.

The joviality ends when we pull out our laptops and start showing them some scenes from a trip to Alaska: The whump of heli blades, the building music, the skier dropping in. It is ski porn at its best, but something is off. The vibe becomes icy as most of the instructors storm out before the first minute is through.

I glance around, trying to understand, but see no sign of help. Rapid, terse muttering from the ski area manager and the head instructor is the only sound. This is North Korea, where you get scared shitless just when you think you’re sweet. It was time for us to go.

ABOVE Groups of locals ice fishing on the Taedong River in Pyongyang.

We sit silently, watching as a rocket shatters the sound barrier onscreen. Moments later, a TV newsreader gives a solemn condemnation. North Korea had tested another rocket just days before we arrived, and tensions are high.

Masikryong is not the most reassuring place to witness such an inflammatory news report. For the past few days, we have harbored a suspicion our room is bugged. Every time we leave the room, we carefully position a shirt over a piece of gear, and then photograph it from a particular spot on the floor. And every time we return, it is never quite in the same position. What are they looking for?

To give us something to pass the time while we watch the rockets screech across the screen, we fire up the camera and attempt to film us watching the television. Almost immediately, the power cuts out, leaving us sitting wide-eyed in the dark. Surely it’s just a coincidence, right?

Over a rapidly draining bottle of rice wine a few hours later, we nervously ask Reewa about the newscast. The rest of the guided group is here as well, listening intently.

“It was surely a weather satellite,” Reewa says, “just like the leader said.”

“The news reports we watched on TV said it wasn’t transmitting anything,” Sam responds, “and that it was unlikely to be a satellite.”

“Well then, that news report lied,” Reewa counters. “Because it’s a satellite.”

“Do you get told before they test one of these rockets?”

“No, they just tell us a few days after, when they want to.”

“Doesn’t that seem odd to you?”

I lock eyes with Sam, and we silently agree to drop the matter immediately. This may be pushing our already borderline conversational limits too far.

Rockets or satellites aside, a storm whips maniacally out the windows, and after the bandana-clad American quietly plucks out a few Van Morrison songs, we head off to bed.

Come first lift we hop on the gondola with hopes of plundering some of the wonderfully spaced trees on the upper mountain. Instead, we find a completely rain-saturated snowpack, sprinkled with stumps and akin to long-expired soup. We still value every goopy turn, savoring the normalcy of being alone on a mountain, darting through the trees, slashing out slushy sprays just as we would anywhere.

Regardless where you go in the world, Mother Nature always rules.

ABOVE A statue commemorating the Workers’ Party of North Korea. The upraised hammer, sickle and calligraphy brush in each of the figures hands represent workers, farmers and intellectuals, respectively.

The next morning we return to our hotel in Pyongyang, and Reewa and Chay tell us we are to visit the modest childhood house of the country’s first supreme leader, Kim Il-sung.

Driving out of the city limits, we enter what looks like a deserted amusement park, complete with frozen water fountains and a sky train. We are told this is a hot spot for North Koreans in the summer months, but the lonely concrete makes it hard to imagine crowds frolicking in the sun.

As our tour continues, I glimpse a large, indeterminant animal in a cage. It warrants a double take, and as it passes behind a building, I make out what looks like a bear with a platypus face. “What was that?” I ask. “What was in that cage?”

Despite their excellent English, the ladies seem not to understand my description. The driver speeds up. I give Sam another look. This is another topic we should drop immediately.

Yet, on the way out, we seem to go out of our way to pass the cage again. It is empty. Was I hallucinating? Has paranoia fully taken over?

Sam is due in Japan on the eve of the late Kim Jong-il’s birthday, and while I feel more off-kilter than ever, I decide to stay for the upcoming festivities. As we drop Sam off at the airport early the next morning, we give each other a big hug. He tells me to stay safe. I wave him goodbye.

I load back into the van, and it suddenly dawns on me I am completely alone.

Being nearly his birthday, the mission for the day is to visit Kim Jong-il on his deathbed. I was told to dress accordingly. Luckily, I was planning on attending a wedding after this trip, and am able to don a freshly pressed shirt, slacks and horrible tie.

The song is a modified version of the “Chicken Dance,” another symbol pulled from the ’50s. The dancers whirl, perfectly coordinated with tune’s monotonous “oom-Pah, oom-Pah.” It is like watching a giant colorful organism expand and contract.

We arrive at the Kumsusan Memorial Palace to an empty parking lot. As I reach for the van door, Reewa grabs me, instructing me to remain inside the van. Soon a cavalry of diplomatic vehicles rumbles up, sporting flags from Russia, Pakistan, Syria and Nigeria. And I thought I was already out of place.

Once the diplomats exit their vehicles, I am invited to join the procession after being reminded that my hands must remain at my sides always. Then I am frisked for any kind of recording device. It’s an unnecessary task. There is no way in hell I am going to risk that.

Pictures and awards cover the walls completely, diplomas from dodgy universities, doctorates from others. Rooms display the various transportation the Kims used during their years in leadership, even the train carriage in which Kim Jong-il supposedly died “whilst signing papers for the country’s well-being.” (Their words, not mine.)

Eventually, we end up before the deathbed. It is dark, the walls blackened by thick velvet drapes. At the center is the body of Kim Jong-il.

He lays rigid in a glass box, his body covered with a red silk sheet and his head peacefully atop a rounded pillow. His face is glossy from an overdose of embalming fluid. I know who he is, but it’s hard to imagine the internationally abhorred leader he once was.

I move with the crowd as they bow four times each, once at his feet, once on each side, and once more at his head. I can hear young girls in the back of the room sobbing. Some weren’t even alive when Kim Jong-il died. I can’t wait to leave.

ABOVE Some things are universal. A fireworks display in the night sky above Pyongyang commemorates the former supreme leader Kim Jong-il’s birthday.

ABOVE The Kims are like religious icons in North Korea. Images and statues of the leaders are everywhere, and our guides were very strict about how they were portrayed in my photos, making sure to check every shot for proper presentation.

ABOVE Kim Jong-il’s birthday is an event celebrated countrywide. There are fireworks and dancing throughout the capital, and students and well-to-do citizens visit Kim Jong-il’s final resting place: A glass casket inside a dark museum, entirely dedicated to the former supreme leader.

The celebration continues in a less morbid fashion. A dance procession to honor the leader is scheduled downtown, and when we arrive thousands of men and women stand idly in front of portraits of Kim Il-Sung and Kim Jong-un. The men wear drab uniforms, but the women wear brightly colored dresses that could easily come from 1950s American.

The music starts and I can’t help but laugh—internally, as I wouldn’t dare show such emotions to my guides. The song is a modified version of the “Chicken Dance,” another symbol pulled from the ’50s. The dancers whirl, perfectly coordinated with the tune’s monotonous “oom-pah, oom-pah.” It is like watching a giant colorful organism expand and contract.

Not long into the proceedings I’m asked to join. And it might actually be fun, if it wasn’t so bizarre, and I wasn’t so scared.

The people are friendly, and I change partner after partner. We exchange no words, just simple looks that left me wondering more than ever, “Where the hell am I?”

Video: CoLab Creative