Adventure

Tajik Dream

High-Altitude Enlightenment in the Pamir Mountains

The Silk Road once traversed these mountains and high-altitude plains, bringing countless riches across Central Asia and into Europe. But Tajikistan’s more recent history of Soviet rule, civil war and societal unrest provides an intense backdrop for a present-day ski mission. Then again, a mountain range with a total lack of information in today’s globalized, screen-dominated society tends to stoke the curiosity.

That unknown is what brought Ryan Taylor to the Pamir in 2016. A ski guide from Temple Basin, New Zealand now living in Japan, Taylor and his ski partner Elliot Smith set their sights on the Fedchenko Glacier, the longest glacier outside of the North and South poles. Equipped with dated Soviet military maps and printed satellite imagery, they ticked off a few lines in un-skied territory, but it was the wild spires of rock jutting even higher above them—and the accompanying library of jaw-dropping couloirs—that all but ensured a second trip.

ABOVE Ryan Taylor crosses one of the wildest ice bridges of the trip on our way back down the Nightmare Icefall. The bridge was about 15 feet long, two feet wide and 50 feet deep, falling off into a cavern of broken ice. This was the only bridge we could find that would get us across the icefall. With anchors set up we went for it one at a time keeping an ear out for any odd sounds of ice fracturing.

That rebate would come in 2019, with Taylor and Smith linking up with another Temple Basin connection, Peter Biskind, now a full-time guide living in Valdez, AK. Biskind rounded out the group with Will Saunders, a Utah-based adventure sports photographer and cinematographer.

From around the globe, the quad-pack convened in the hectic streets of Dushanbe—Tajikistan’s capital—in May of 2019. The crew had a few ski objectives, but their eyes were focused on Taylor’s “Dream Line,” a shot he describes as a “twisted, re-curving couloir like something you would hallucinate on an acid trip.”

Chasing the Tajik dream through a month of the crew’s field diaries, here is their story, in their own words.

ABOVE Outside of our dom, Peter Biskind pours out water after rehydrating kidney beans. Rehydrated beans were the staple of most of our meals and oftentimes they wrecked our stomachs. These doms are mud huts for locals to use in the summertime when they bring their livestock up to the plateau. Lucky for us, we were there in the snow, so the locals let us use their dom as a base camp for the expedition. From here we would tour seven miles or so into the mountains and set up advanced base camp.

Peter—Day 1

The blurry first 48 hours began in the San Francisco airport. Two flights later, I arrived in Istanbul. I met Will [Saunders] en route to the gate to Dushanbe and searched for Wi-Fi and water to no avail.

We took off at 8 p.m. (11 a.m. my time), the old delirium of time warp strengthening its grasp. A little napping and—poof—we were in Dushanbe in an hour-long visa line. We missed our ride, but immigration and customs were a breeze. Odd taxi ride negotiations. Note to self: Always set a price and destination before, even if you don’t speak the same language.

Some amazing introductions at the hostel—Will had never met Ryan [Taylor] or Elliot [Smith]. Jump in the deep end, boys. The team hit it off, phew!

A few hectic bazaar shopping sessions and 80 kilograms of food acquired. At the final market, an Interpol agent stopped us and said to keep our heads on a swivel because the Taliban had decapitated an American less than a year ago. He didn’t give us any more advice, which scared us. Time for some beers.

ABOVE TOP TO BOTTOM

A big part of expeditions is being self-sufficient in every single way possible, including medically. We packed an extensive med kit and did our research on how and when to use each thing in case of an emergency. We had everything from high-altitude meds to simple sleeping pills. Health plays an even more important role when you are hundreds of miles from any sort of rescue.

We carried a simple kit of tools for repairing ski gear, electrical gear and everyday items. With a successful trip, we did not have to dive too deep into the kit. Elliot was the mastermind on the trip whenever we needed to fix or rewire something.

Elliot—Day 3 (my birthday)

We played Tetris getting all our gear into [Ryan’s fixer friend] Zafar’s now-familiar Land Cruiser. The former army doctor and our Tajik jack-of-all-trades assured me the brakes are working this time. The mood was good on the travel to Jilandi, and as the mountains came into sight, I couldn’t imagine a better birthday present.

When we arrived, we realized our calls ahead to discuss horse transport and a potential base camp yurt had not been as fruitful as we’d hoped. Waiting to greet us was Mubien, the man that had solicited bribes from me on our last trip.

Much hand waving, map pointing, broken Russian and stick drawings of horses later, we arranged two horses, one donkey, and Mubien, Kishmatolo and Dolat to accompany us. Business done, we gathered at Zafar’s house for chai, naan and catch-up with old friends. The hospitality of the Tajik people is humbling and we are very grateful for it.

ABOVE The town of Jilandi is about 20 miles from the base of the mountains where we skied. There must have been less than 100 people living in simple homes with hints of old Russian items like this car. We spent one night here with a local family before we set off to the mountains. The people were incredibly caring and excited to give us a place to lay our head and share a naan and yogurt dinner.

Will—Day 4

Today was a long fucking day. Supposedly only a five-mile portage to the dom—the mud hut we’ll be using as base camp—but the terrain was intense. Lots of vert—think mud, scree fields and post-holing.

Everyone was fully loaded. I thought we were going to watch a horse break its leg or a donkey die. This part of the expedition felt especially selfish, making locals use their limited resources to help us, but they seemed to have a good time. Our donkey did a barrel roll hauling our ski gear, so we took turns carrying bags. Oh! And we saw lots of bear tracks.

The mountains look like Everest. Absolutely mind-blowing that we will be the only four people among these peaks for the next month.

Large lock on the door of the dom. Our hearts sank. We waited in the cold for Elliot to catch up. The villagers told him the door was locked and gave us permission to remove it. Elliot wielded a BD Venom ice axe and slid the pick under the latch, quickly prying it out of the wood.

Dehydrated, feeling wrecked, passed out in the mud hut.

ABOVE To get our bearings the first day we went on a small tour during hot, bluebird weather. This simple line—with Ryan Taylor skiing it here—got us excited for the big objectives to come.

Ryan—Day 9

Up around 04:00 a.m. Our approach followed the crest of the moraine with the glacier far below.

We’d eyed the Warp Couloir from our rainy base camp in 2016—a plunging 3,600-foot shot through undulating mountain rock—but only had four ski days during our soggy month in Tajikistan. To be back here (and ski!) is a satisfaction worth the years of “what-ifs.”

The exposure to the hanging glacier above could only be partially avoided, but we did our best, climbing hard left. The serac and the fold of red rock supporting it resembled a blue monster cradled in the arm of a giant. Best not wake it up.

Large avalanches ripped down the east face of an adjacent peak as the first sun hit us. The intensity of the rays at altitude instantly sent temperatures soaring. With several hundred meters to go, we had two to three hours to get up and down our west-facing line. Were we too late?

In the heat of the day, small rocks whizzed past at impressive speed. A pebble stung me in the thigh, pushing me off balance. “ROCK!” I shouted, watching one fall off the wall above Pete and Elliot and accelerate. Will and I froze. I poised myself on front points, ready to leap out of the way. Will leaned right and I leaned left as it narrowly sailed between us.

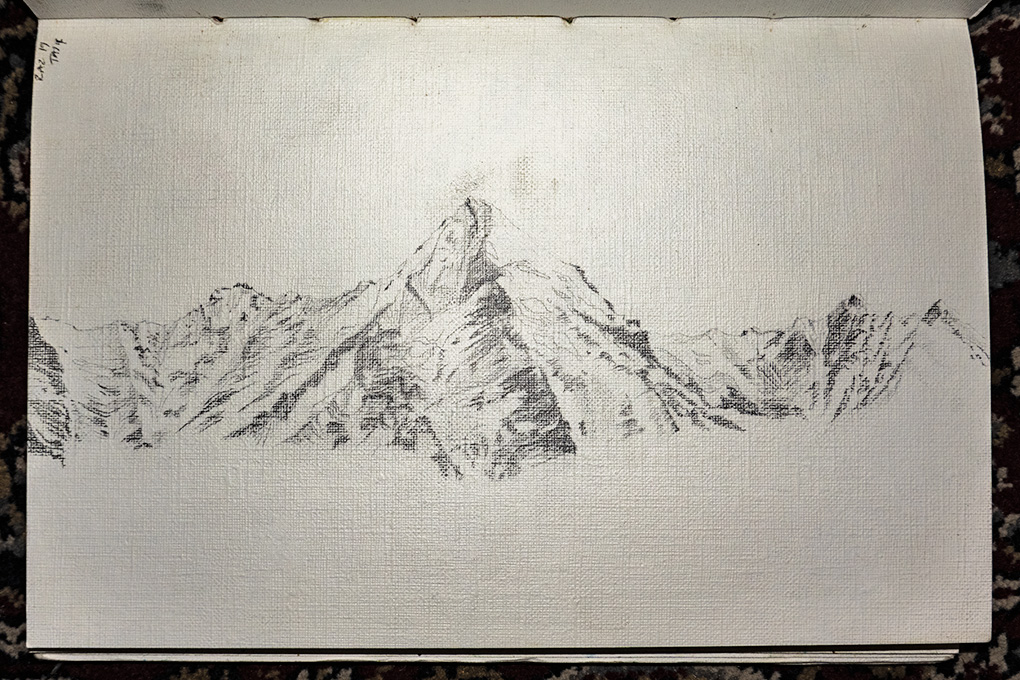

ABOVE During the rest days, we would fill our time with anything from art to snow baths. Ryan Taylor drew this realistic sketch of the peak 5468 (Mt. Hood) view from the dom. Ryan wanted to ski the 6,000-foot vert, 45-degree face, but we were not able to make it over there before the end of the trip.

Ravens screeched from the cracked spire above as the guys topped out. They walked onto a snowy platform that looked into the adjacent valley and glacier, and from there we got our first views of the Dream Line. After countless years studying imagery, I could have never imagined it in reality. Incredible.

We were all dehydrated, tired and having trouble thinking straight. After a long, circular conversation, we decided I would ski first while Will shot.

I didn’t hold back and skied the line as hard as I could, starting with jump turns in the narrow section before opening it up, enjoying the adrenaline and speed after a slow climb. As I neared the serac, I pulled over for a break, the sweet sensation of oxygen rushing back into my brain.

After Peter and Elliot dropped, I waited for Will. Together, absolutely fizzing, we enjoyed corn turns down to the bottom.

We rested in tents for a few hours and got rehydrated. Cruising the low-angle terrain back to the dom, we stopped to fill bottles in the stream melt of the glacier in the fading evening light.

ABOVE Elliot Smith makes a few hop turns on the 45-plus-degree entrance of the Warp Couloir. The start of this run was tight and steep, eventually opening into the heart of the mountains. The descent had to be quick on this line because there was a massive hanging serac above us.

Will—Day 11

Woke up at 1 a.m. wondering why the fuck we do this. Pete made us coffee and muesli. Crampons on, skis on our backs, we made it to the first saddle right at sunrise. From there, 2,600 vertical feet of steep approach to our ski line with some moments of climbing and 60-plus-degree pitches of inclined ice.

The Shield is a north-facing glacier sitting on top of a 16,400-foot mountain. The glacier was mostly covered, but some large patches of glacial ice poked through. By noon, we summited, but clouds were beginning to swallow the area. Storm coming.

I found a couple of pitons from an old Russian climb. We didn’t get the first ascent, but we did get the first descent. The ski was epic—a mix of hippie pow and patches of luminescent ice.

I broke through a snow bridge and sunk shin deep in a glacial creek on the ski out, soaking my feet and boots. We still had an hour of skiing back to the dom; my feet were fucked and the blood rushing back to my appendages hurt like hell.

ABOVE Ryan, Elliot and Peter make their way up the Dream Line. The 100-foot walls of the couloir snaked their way to the summit, towering over us. The snow stayed extremely cold and there was some windblown fresh on top, making the 3,000-foot boot pack a bit more avalanche prone.

Peter—Day 13

Chill at the dom. New water hole! But 30 days on an agricultural plateau in a developing country without water treatment is a bit risky. Understatement. We all got a stomach bug and garden hose diarrhea. Imodium and Pepto were invaluable. Achy and sick for 24 hours at least. I am sick of beans.

Will—Day 14

I knew going into the trip that we would get sick, that it was bound to happen. The trip is starting to challenge me mentally. A little homesick, for sure wishing I was with friends and family. Lots of angst about my career, but I am doing my best to stay present. Also, happy Mother’s Day <3.

ABOVE Mubien takes a break with his horse during the hike into base camp. The locals helped us carry gear into the mountains using two horses and one donkey. Due to the deep snow, we often had to take all the gear off the animals and shuttle the bags ourselves. In the end, they were able to make it about 90 percent of the way, and we shuttled the rest of the gear. The locals were our last human connection while out in these mountains. We looked forward to seeing their smiles and hot tea. Communication was simple, just smiles and gestures, as they only spoke Tajiki.

Elliot—Day 15

Had a good rope skills clinic with Pete before our trip up the icefall, super happy to have his experience in the party since we have never been on a rope together before. The clinic was interrupted by me finding a lost-looking pika (a rabbit-like mountain dweller) in the gear annex of the dom. A rush ensued, as we had been without fresh meat for weeks.

The hunt was more opportunistic than planned, and we spent a lot of time chasing the terrified pika around with ice tools until we had it cornered. Pete hastily improvised a spear with a ski pole, guide strap, and climbing knife and we put the poor creature out of its misery. Pete cleaned it. After four hours of slow boiling, the meat was still tough with the adrenaline of the poor pika, but surprisingly tasty.

We later discovered that pikas carry bubonic plague and eating them is inadvisable.

ABOVE Goats are the most common form of livestock around Tajikistan. When driving you are guaranteed to get stopped by a thousand goats crossing the road with their owners. Most meals involve goat as well.

Will—Day 17

We didn’t get up as early as I’d hoped. They say travel through ice when it’s most cold and solid, but we got to the base of the icefall around 10 a.m.

There were two routes up. One required a traverse under a massive rock wall that had two potential serac climbs. We went with the other—a direct route up the heart of the icefall. Pete led. The first piece was mellow, but the next section brought us into a massive ice wall corridor, 50-foot seracs surrounding us from every angle. Suddenly, we were all on edge.

The only way through was a true ice climb. Pete climbed with 50 pounds on his back and skis. I nervously snapped pictures to ease my mind.

An overhanging block kept hitting our skis, so we topped out like beached whales. Elliot screamed profanities the whole way. We were 50 feet up on top of a massive serac, the crevasses below deep and dark. We approached a bridge of ice three feet thick and two feet wide, crossing a 15-foot-wide crevasse to the next serac. It was exposed with long drops into a black abyss. Pete led as the three of us prepared to catch his fall on a single ice screw. Luckily, the bridge held.

ABOVE By the end of our trip, what was once snow-covered had turned into a lush plateau filled with goats and their owners. The locals start making their way up the plateau as the snow melts and they can graze their goats. These locals are extremely rugged, living off the land and tending their goats, while their herding dogs are the size of wolves and very intimidating.

My turn next. I took a breath, then inched forward. Halfway, my rope went taught. Ryan had decided to clean the gear right as I was in the middle and forgot to give me slack. Those five seconds standing on that fucked piece of ice lasted an eternity. “Clean that shit later! Give me rope!” I made it across, shaking.

After seven hours, we made it through the gnarliest icefall and found camp at the base of the coveted Dream Line—like something out of a Dr. Seuss story. This was it. We set up tents in the middle of the glacier surrounded by our alpine amphitheater.

Weather coming in and we’re unsure if we’ll get a break to summit.

ABOVE Ryan Taylor deep in the belly of the Nightmare Icefall. Navigating this icefall was one of the gnarliest parts of the trip, taking us over seven hours surrounded by seracs, crevasses and zombie ice. Peter made an incredible lead through this maze. We named it the Nightmare Icefall because it was the one thing we needed to go through to get to the Dream Line.

Ryan—Day 19

It’s still windy, but this morning the clouds dropped to become an ocean below the icefall. The sun was rising through the U-shaped summit, the morning rays casting long shadows and backlighting our peak as spiraling rotors of powder dump into our Dream Line.

Although a beautiful sight, this large amount of snow—the biggest storm of the trip—is concerning. If there’s a large avalanche in the couloir, the result would be catastrophic. Soon the clouds rose and engulfed us again.

Peter—Day 21

We awoke at 1 and 3 a.m. to assess the weather. No one was sleeping well because the wind was howling at camp. Can only guess what it’s doing up high. We rechecked the forecast—still looking better for tomorrow and next day, but then shutting down in 72 hours. We need to send and then retreat through the icefall before the next storm hits.

More stove problems. Not just clogged jets, clogged fuel line. We cut apart a USB cable to poke and clean the line. Reality of low fuel, food dwindling and a third day of weather hold. Couldn’t see 60 feet out of tent.

ABOVE Advanced base camp sitting right at the base of the Dream Line on an active glacier. We planned on being at this camp for just a day or two but we ended up getting stormed-in for 48-plus hours, leaving us stuck in the tents anxiously waiting for a break in the weather.

Ryan—Day 22

Awoke at 1 a.m. to no wind and no clouds. A full moon hovered at the head of the glacier, bright and reassuring. We cooked our last breakfast and howled under the beaming moonlight.

I triple-checked my gear before getting on the end of the rope. We contoured around the top of the icefall to the entrance of the line that I had skied in my mind for years. The moon was dropping behind the peaks, but moving directly into our couloir, as if by plan.

Stashing our gear and transitioning to crampons, we climbed through a narrow chute in the wall to access the couloir proper. Our peaks were now orange in the morning alpenglow and the glaciers turned a deep green. The twisted rock bands, spires and hanging glaciers seemed closer to a van Gogh painting than reality.

In the frigid conditions, Elliot was having issues with his feet. We put our warmest layers on, dug a platform, and he warmed his liners inside his jacket while I tightly clamped his feet under my armpits. It wasn’t very pleasant considering neither of us had showered in weeks, but it had to be done. I was determined that we were all getting up there.

Gradually feeling returned, so I pushed up the couloir after the others. Eventually, I took the lead and went full beast mode. All I felt was pure joy. My longest running ski mountaineering ambition was within reach.

But 300 feet from the top, the snow got slabby. I decided to gain more distance on the others. If I triggered a slab, there would be less of a chance they would be taken down with me. I peeled out from the wall, climbing straight up.

I topped out at 17,400 feet. The couloir ended abruptly at a razor-backed spur, plunging back sharply toward the glacier. The sun had just peaked into our line—we had nailed the timing.

I congratulated the boys as they arrived. We were privileged to be here. I gave Elliot a hug in my altitude-drunk state.

The temp was near minus 4 degrees Fahrenheit. We finished some remaining coffee, got the group selfie, and started getting ready.

I dropped first, making slow, careful turns through the slabby snow until it became fluffy and deep. I opened it up, enjoying the deep powder and keeping enough speed to escape any potential slide. Cutting back beneath the safety of the wall, I hopped on the radio.

All was well, I was ready to ski the couloir proper. I had spent years dreaming about skiing this line, and here it was in powder conditions.

I traversed out toward the steeper, loaded side of the couloir, hoping it wouldn’t pop. The panel was slightly wind-packed but it didn’t feel hollow. I took the chance and submitted to gravity, opening up to the fall line and making GS turns. Nothing was moving so I let loose, skiing to the limit of my tired legs.

Rounding the recurve, the snow became warmer and denser. I collapsed at the gear stash and sucked air. My brain was in a state of overload. I howled at the top of my lungs.

I hopped back on the radio: The crew needed to get going quick, things were heating up. Fast.

Grabbing my gear, I skated back across the glacier, struggling to see the boys skiing down the couloir, tiny ants against the towering terrain.

above Elliot Smith skiing the Dream Line after Peter ski cut a six-inch slab down the chute. The towering wall behind him was filled with shapes and color that resembled a massive uncut gem.

Elliot—Day 25

Two days ago, Ryan debated staying to ski another line but was outvoted. After eating our last cereal and milk powder for breakfast, we began the icefall descent with about 10 gummy chews between four of us and 80 milliliters of fuel left. Pretty good rationing, really.

We thought the descent of the icefall would be faster since we could rappel down a more direct line, but it still took eight hours.

Got to the dom just at dark and collapsed into bed.

Yesterday we had a relaxing day in the sun and cooked a feast with our remaining salami and beans. Started drinking our brandy and vodka and found it went well with the codeine cough syrup Will had brought.

Apparently, people buy the stuff for a grand a bottle. Finished the night suitably drunk having an impromptu rave in the dom.

Woke up hungover to a sunny day, but rain is in the forecast and the food situation is looking pretty bland.

above Ryan Taylor makes his way down the bottom half of the Warp Couloir. Ryan has a history in ski racing and it shows. He skied every descent hard from top to bottom, making the most out of the hard-earned turns.

Pete—Day 26

Dolat and Kismatolo, our two local horsemen, arrived with two horses—and food! They stayed the night and we ate after sundown since it was Ramadan. They ate again in the middle of the night while we slept.

Elliot—Day 27

We gave our “rescue party” our extra gear, and Kishmatolo is stoked about the Bluetooth speaker. Walking out, we meet some nomadic shepherds coming to graze their animals on the new grass. One stares at us tight-lipped as we walk past their camp, holding a blood-soaked knife from cutting an abscess out of a lamb tied up next to the tent.

Wandering the same mountains, we look pretty out of place with our bright clothing and ski packs. In the village, our friend Zafar is waiting, his wide grin welcoming us back to the world below.

This article first appeared in The Ski Journal Issue 14.1.