Profile

Vasu Sojitra

Lift as You Climb: Vasu Sojitra’s Kinetic Energy

Vasu doesn’t just get around though. He’s one of the most accomplished adaptive athletes on the planet. In addition to emerging as a premier (and fully self-taught) backcountry skier in the Beartooth and Bridger ranges of Montana, he has climbed the Grand Teton, earned skateboarding shout-outs from Tony Hawk and Nyjah Huston, and become the first adaptive athlete on The North Face roster.

But to really understand Vasu’s journey, it’s important to look, once again, at the tattoo. The lotus flower is important in Hindu and Buddhist cultures, a flower that can grow and prosper from any body of water, no matter how dirty or polluted. As a disabled person and first-generation Indian American, Vasu has taken the lotus’ resilience to heart, working his way up from the small ski hills of his Connecticut childhood to some of the most challenging peaks in North America. In addition to his physical achievements, he’s found his calling working as an adaptive ski coach, mentor, and program director, while co-founding Inclusive Outdoors Project a collective dedicated to promoting inclusion and representation for people of color, people with disabilities and the LGBTQIA2S+ communities within mountain sports. He is also a founding member for The Outdoor F.U.T.U.R.E Initiative, and a Disability Access strategist partnering with organization like The Avarna Group, In Solidarity Project and independently.

“I want to get more people involved, shorten the hurdles people face to get into skiing, and help them to find that same sense of freedom,” he says. “I’m trying to lift as I climb.”

It’s a mission Vasu approaches with zeal, using the platform he built from his athletic success to amplify voices drowned out by the static of the status quo. In the oft-homogenous realm of outdoor culture, the fight has been frustrating, even isolating at times, but as society grapples with the ugly truths of systemic inequality, Vasu knows there’s more on his shoulders than just some pretty black ink.

On a June afternoon, Vasu Sojitra stands in front of his line on the Gardner Headwall in Wyoming’s Beartooth Mountains, home to some of the finest spring and summer skiing in the United States. Slashing down a 45-degree slope minutes earlier, he’d left his photographer scrambling to keep up. Photo: Aaron Teasdale

Vasu is kinetic energy. Sitting in his Bozeman, MT apartment on a sweltering July afternoon, he’s balancing a phone between his shoulder and ear while rapidly firing off emails from his laptop. He’s got mountain-man stubble and speaks calmly through a natural half-grin, arranging a rafting expedition down the nearby Madison River, while his emails range from organizing Zoom panels with adaptive sports organizations to planning an attempt of the Teton Grand Traverse (an 18-mile, 12,000-foot-vertical-gain hike that normally takes three days for the ultra-fit). It’s just a few weeks after he left his job at Eagle Mount Bozeman, an adaptive recreational organization where he was the adaptive sports director for six years, and I’m not sure he’s stopped to take a breath.

In the whirlwind, he hands me a box of footwear, asking me to follow him to his Toyota Tacoma. The box, I realize, is full of right shoes.

“I don’t really need those,” Vasu smiles, basking in his twisted humor and my deer-in-the-headlights expression. The shoes are headed to Patrick Halgren, an adaptive skier and friend Vasu jokingly calls his “sole brother.” Trail runner, climbing shoe, soccer trainer, road-bike cleat, ski boot—each shoe a vignette of a man who can’t sit still.

Vasu finds late-afternoon powder stashes while on his lunch break from work with Eagle Mount Bozeman, the adaptive recreation organization where he was the program director from 2014 to 2020. Bridger Bowl, MT. Photo: Jason Thompson

Vasu was born in Hartford, CT, the second son of immigrant parents. His mother worked as a microbiologist at the hospital where Vasu was born and his dad owned a few local convenience and spirit stores, but that work was put on hold when Vasu turned 9 months old. To stem a blood clot caused by sepsis, doctors amputated Vasu’s right leg just below his hip socket. After the surgery, the family moved back to India to be closer to their grandparents, and Vasu’s mother Rama constantly worried that her youngest might fall behind other kids his age. Vasu, on the other hand, was more focused on keeping up with his older brother, Amir. He consistently broke his prosthetic leg running and playing and wanted to try any new sport he could get his hands on.

“We didn’t tell him he couldn’t do something,” Rama says. “He needed to decide his own limitations.”

After returning to the States at 7 years old, the youngest Sojitra quickly took to swimming and soccer, and even taught Rama how to ride a bike. When Amir picked up skateboarding, Vasu followed suit. When his brother wanted to play ice hockey, Vasu tried out and made the team as a goalie.

In the fourth grade, he decided to stop wearing his prosthetic after tripping on its cumbersome hardware and opening a gash above his eye in front of all of his classmates. After trying to be like his able-bodied peers for years, Vasu was done fitting the accepted mold.

“I wanted to look like all the other kids, but I was always taking [the prosthetic] off when I got home,” he says. “I got frustrated. I wanted to be myself.”

The Sojitras enjoying a family trip to Washington, D.C. in the early 2000s. Vasu’s mother was a biochemist and his father owned several local businesses, so Vasu and his older brother, Amir, spent lots of time entertaining themselves with skateboarding, soccer and, eventually, skiing and snowboarding. Photo: Sojitra Family Archive

Shortly after, the Sojitra brothers discovered the mountains. On the urging of a family friend, the boys—Vasu on skis and Amir on a snowboard—took their first lessons at Ski Sundown in New Hartford. Rama says none of the Sojitras were quite sure how Vasu was going to make it work, but that same day he met a one-legged skier and saw what was possible on snow. The Sojitras found an adaptive ski program for 10-year-old Vasu in New York, but it was too late—he was already teaching himself.

Skiing didn’t come to him overnight, though. Vasu says it took him eight to 10 years to really get the hang of the sport, from learning how to maneuver his outriggers—poles with skis attached that function as his balance points when going downhill—to skiing moguls on a single leg. But Vasu was stubborn—a trait he says continues to push him in his adult life—and forced himself to try and keep up with his brother and friends. “There were a few times when everything connected, and that flow state is addictive,” he says.

Vasu eventually attended the University of Vermont to pursue a mechanical engineering degree—and feed his evolving snow addiction. He participated in the UVM Outing Club, spending his weekends skiing tight trees at Jay Peak or crushing bumps at Sugarbush Resort. During that time, he also picked up backcountry skiing, attaching a snowshoe extender plate to the bottom of his outriggers for greater purchase uphill, and slapping a skin on his single ski.

“It’s not impressive to watch him as an adaptive athlete; it’s shocking to watch him as an athlete,” says Tyler Wilkinson-Ray, an outdoor filmmaker and producer who met Vasu playing pickup soccer at UVM. “I think that’s a completely unnecessary qualifier. He is a freaking insane athlete.”

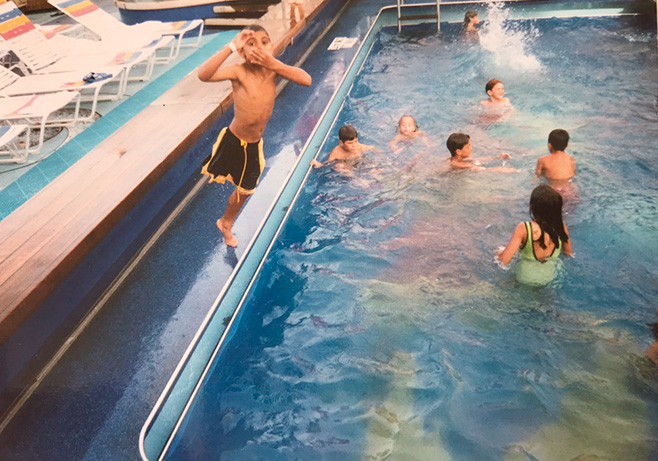

Vasu on a Disney cruise where he first learned to swim by jumping into the deep end. He briefly competed in the early 2000s, but lost interest when the mountains started calling. Photo: Sojitra Family Archive

As Vasu continued to improve his skiing, he found community in the mountains. After years of feeling disconnected from the world around him, Vasu found comfort in being a typical college ski bum—a life that revolved around ski movies, finding cool (and cheap) new gear, and getting out on snow as much as possible.

Still, his story was unique, and it began to propagate well beyond the Green Mountain State. After he and Wilkinson-Ray debuted a biographical short film titled “Out on a Limb” at 2014’s Banff Film Festival, Vasu started to get noticed in the outdoor industry. He moved to Bozeman after graduation to pursue bigger mountains, where he met legendary mountaineer Conrad Anker at the local climbing gym. Anker says that in addition to the young athlete’s physical abilities, he was “impressed by his intellect and drive,” and introduced him to The North Face.

There was very little Vasu couldn’t do on skis. He started skiing switch. He landed a 720. Yet just as Vasu was hitting his stride as a professional athlete, he started to notice cracks in the outdoor culture he was helping to cultivate.

“There are lots of other adaptive athletes that don’t get the traction that I’m getting, but why?” he asks. “What did I do that’s different?”

Vasu struggled to understand why there were so many adaptive athletes in the mountain community, and so little representation at the pro and organizational level. Something needed to change.

After tinkering with early prototypes as a student at University of Vermont, Vasu, who has a degree in mechanical engineering, has customized his outriggers with an ice axe for climbing steep pitches and snowshoe extenders for greater purchase during long backcountry trips. Photo: Kade Krichko

By the time he summited the Grand Teton in 2014, Vasu had already begun working with Eagle Mount Bozeman. The Montana adaptive recreation non-profit allowed Vasu a chance to work hand-in-hand with the adaptive community. Though he had never been in an adaptive program growing up, he had volunteered with Vermont Adaptive Sports before moving west, and took on a director role with Eagle Mount. That meant getting more than 200 Bozeman-area adaptive athletes on snow every winter—most of them skiers.

“I’ve felt that state of freedom [as a skier], and now I see that similar mindset with these kids that have disabilities. Even a run that we see as going back to the lodge, they can feel that,” Vasu says. “[We] focus on people’s ability and use that as a ripple effect to start engaging in activities that provide self-growth and self-resiliency to be able to then connect with peers, friends and family.”

Whereas the pursuit of the human limit in the outdoors has felt more and more self-serving for Vasu, he says adaptive sports measures its successes and failures as a collective—an approach that reminds him of his upbringing in community-based Indian culture. The individual can only flourish if the entire organism succeeds. That communal aspect connected Vasu with a large network of disabled athletes, relationships that eventually forced him to reevaluate his role not only as an athlete, but also as an advocate.

“It was a very transformative time in my life and it still is,” Vasu says. “It was super uncomfortable, but so necessary… a little bit more of a deeper dive into how we interact with each other as humans.”

“Vasu skinned across this ridgeline near the Montana-Wyoming border and dropped into this late season line a few days after the road opened into Beartooth Pass. Everyone we bumped into on the road already seemed to know Vasu. That’s Bozeman celebrity status.” June 2020 at Beartooth Pass, MT. Photo: Colin Arisman

Realizing that his position as a professional athlete made him unique, Vasu began to find his voice. The Instagram posts he sent out to his nearly 38,000 followers went from whimsically aspirational to informative and social justice based. Pictures of him topping out on a dramatic ridgeline or slashing down an alpine couloir were accompanied by quotes from civil rights activist Angela Davis or an essay denouncing ableism (a belief that able-bodied people are superior, which is used to discriminate against people with disabilities).

The evolution was enough to set off alarm bells in the mountain sports bubble, a population Vasu often describes as “complacent” when it comes to certain social issues. Some followers questioned his motivation, and he says more than a few asked him to tone down his “aggressive” messaging.

“One of the things that Vasu does well is that he doesn’t see his job there to sugarcoat the conversation so that white people can feel better about their sport. Vasu’s job in skiing is not to make us feel better about the sport of skiing,” Wilkinson-Ray says. “Sometimes people don’t know how to respond. They think he’s angry. He’s not an angry person.”

“I can’t take off my skin or not be disabled; I will always have both of those things,” Vasu says. “I have a hard time biting my tongue when it comes to a lot of this stuff because it really affects those underrepresented and marginalized communities, the ones I grew up in and which have affected my parents as they immigrated.”

LEFT TO RIGHT When Vasu isn’t pursuing his own athletic endeavors or coaching, he is working to uplift the adaptive and BIPOC communities. That type of help comes in many different forms, whether it be connecting athletes to resources, organizing affinity spaces, or sending a box of new right shoes to an adaptive athlete friend in need. Photo: Kade Krichko

Made of titanium, Vasu’s ninja sticks take a beating. For years, he snapped crutches while playing sports, but after making the upgrade to a stronger crutch as a teenager, Vasu opened a whole new world of ski, skate and trail possibilities. Photo: Kade Krichko

For the adaptive athlete, his message was not one of aggression, but rather of survival. After the 2016 election, Vasu suddenly saw his Indian roots—and the roots of minorities across the country—as a much larger cultural barrier. Feeling isolated at the intersection of his race and his disability, Vasu decided to create Earthtone Outside MT, a nonprofit focused on the inclusion and representation of people of color in the outdoors, with some friends in 2017. In addition to aligning with traditionally Black-run organizations like the Brotherhood of Skiing and Climbers of Color, the nonprofit affinity space organizes chats and outdoors clinics, and last year hosted the first ice-climbing clinic solely for participants of color.

“It’s not ever about the activity or the sport; it’s about this shared lived experience,” Vasu says. “It’s an amazing way to grow empathy, whether it be through skiing or any other activity or form of communication.”

With his nonprofit work and activism beginning to take over his day to day life, Vasu has found more peace than ever in the mountains. In the summer, that means 20-mile trail runs and long road bike rides, and in the winter, well, that’s still all about the skiing. He says his work with the adaptive community has given him a different appreciation for sliding on snow, and calls his pro athlete life, “self-care time.” In Vasu’s mind, skiing gives him the confidence to take on the challenges facing his communities, and each dose of the alpine provides a vital boost of energy for the long fight ahead.

Using his ninja sticks, Vasu laces a 360 flip at the Bozeman Skatepark during the summer of 2019. He often posts his skate videos to Instagram, and has had his posts shared by Tony Hawk and Nyjah Huston, among others. Photo: Rachel Leathe/Bozeman Daily Chronicle

When George Floyd was killed by Minneapolis police in May, our country’s history of racial injustice was thrust into every living room in America. The recoil was swift, even within the outdoors world. Vasu’s phone started ringing. Friends, other pro athletes, brands—people wanted to know what could be done.

Anker, who has been Vasu’s professional mentor since they met in 2015, says he has had several conversations with the 29-year-old since Floyd’s death. “He’s taught me about structural racism, about how the system is built the way it is,” Anker says. “To have a friend in the outdoors community that is experiencing that firsthand… to have someone I can talk to from a more diverse background—there’s a real benefit for all of us there.”

Vasu speaking about the importance of incorporating disability justice into societal and cultural movements at the Bozeman Black Lives Matter rally in the spring of 2020. In recent months, he has continued his work in the BIPOC and adaptive communities, working toward a more equitable outdoors industry. Photo: Kt Miller

Vasu and Wilkinson-Ray believe that benefit can extend beyond a few chats around the proverbial campfire. Together with documentary filmmaker Faith Briggs, the pair is planning a consulting operation of sorts for people of color, the disabled and other marginalized voices in the outdoor industry. The goal is to promote representation and inclusion—getting more models of color into catalogs or organizing sponsored introductory clinics in indigenous communities, for example—while weeding out potentially harmful rhetoric in order to help companies and individuals improve their practices on a continual basis, rather than a reactionary one.

“There’s a lot of hard conversations, for sure,” Vasu says. “But we need to figure out how to work together in a way that starts helping and supporting folks and connecting with their identity to push the needle forward.”

Vasu left Eagle Mount and Earthtone Outside MT this spring (moves expedited by COVID-19), but considers both important steps toward tackling his newest challenges. In addition to consulting, Vasu hopes to climb and ski the Grand Teton, using the mission to raise awareness of the social issues he has found himself at the forefront of—challenges that even that stubborn boy from Connecticut would have a hard time grasping all these years later. It’s a steep ascent that is as fulfilling as it is exhausting, but if his decades-long pursuit of skiing is any indication, Vasu will find a way forward.

Vasu shredding powder in a moment of pure freedom at Bridger Bowl, MT. It brings to mind one of his favorite quotes from Australian disability activist Stella Young: “Disability doesn’t make you exceptional, but questioning what you think you know about it does.” Photo: Jason Thompson

This article first appeared in The Ski Journal Issue 14.2