Memoriam

Warren Miller: Innovator, Inspiration and Icon

1924-2018

The message is still on the office answering machine from about a decade ago, and we’ve been careful to keep it saved ever since.

“This is a lot more than a publication; this is beautiful!” the man on the machine espoused. The voice was utterly unmistakable, and it was validation on a spiritual level; like getting an audio high five from the Buddha himself. Warren Miller had blessed us.

I’d grown up watching every one of his films every winter, often with three generations of my family and several times in the Sun Valley Theater, so hearing his voice, speaking directly to us through the answering machine, was surreal. And a decade later, it is only more so.

Our publications and our staff would go on to develop a real and meaningful relationship with this godfather of American ski culture. After this first voicemail, I ended up having several further conversations with Warren, and eventually—on a freezing November day nine years ago—then-photo editor Grant Gunderson and I took a small Cessna across Bellingham Bay to the Miller home on Orcas Island. His son-in-law Colin Kauffman picked us up, and we spent a delightful and stormy afternoon with Warren and his wife Laurie in their classic PNW-style beach home. He shared tales of long-forgotten Austrian ski pioneers and Malibu surf renegades, showed us artifacts and photos, made jokes, and stoked the fire. He and Laurie made us feel as welcome as welcome can be. That visit, and the accompanying conversations, soon appeared in The Ski Journal as the longest story we’d ever run.

A few months after his interview appeared in The Ski Journal, he reached out to ask if we would be interested in having him write for us. Again, he reached out to see if we would want him to write for us. So now the Buddha wanted to join our monastery. With demure gratitude we absolutely accepted, and for several years he wrote pieces for our readers—75-plus years of ski life, pouring out onto the pages of each issue.

Over the years we have won several publishing and ski industry awards for our work, received numerous accolades and the respect of our peers. But nothing was so gratifying, so verified the sense we had arrived, than when Warren Miller visited our spartan production offices in Bellingham. He walked around, admiring the posters, skis, dogs and other artifacts and snow paraphernalia, and declared: “This is perfect!”

We affectionately called him “our oldest intern,” and he became a true friend to The Ski Journal.

Last Thursday morning, I learned he had passed away in the night at his home on Orcas, surrounded by family, at 93 years young. I was preparing for a reading at a literary event in Seattle that evening. The story I wrote specifically for that event was, serendipitously, about living in Sun Valley in my 20s with a group of friends, all of us semi-homeless and dedicated to skiing and snowboarding. When it came time to read it, I stood and dedicated the piece to Warren and his family, noting that he paved the way for this lifestyle 75 years prior. It wasn’t a ski audience, and I wasn’t entirely sure what the reaction would be. The moment elicited the evening’s greatest applause.

Warren was a giant. In addition to his film library, his contributions were many. He served his country in WWII, finding himself swimming in the Pacific courtesy of a Japanese submarine. He founded non-profits dedicated to assisting young entrepreneurs, delivering ski gear to far flung locales in India, and other worthy endeavors. He put blind skiers, para skiers and other differently abled skiers in his films, well before there were lessons and competitions available for them. He absolutely loved kids. And, as 75 years of skiers can attest to, he told stories like no one else.

I needed a few days to reflect and mourn a bit before I could pen something for Warren. And really, there is simply no way to summarize his life or contributions in a few hundred words. As such, we are running our original interview with him, at full length, for you to enjoy.

To the WME staff, to Laurie, to Colin and to Warren’s entire family, our thoughts and prayers are with you.

And to the man himself: Thank you.

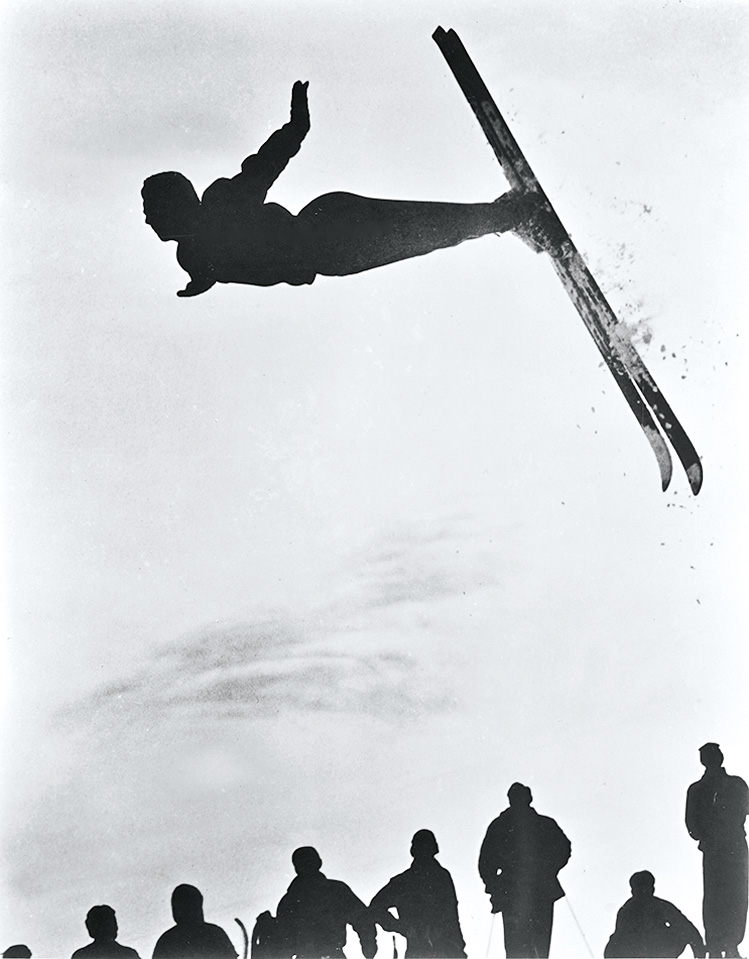

ABOVE Before the slow dog noodle, the Wong banger, Bobby Burns, or ski ballet, Warren was doing freestyle turns like this one in Sun Valley, Idaho, 1947—his first year living in the mountains.

A Taste of Freedom

Warren Miller: 70-Plus years of Skiing and Believing

Intro Jeff Galbraith Words Warren Miller

Anyone who has skied for any length of time in this world has a Warren Miller story. The mere mention of his name almost always elicits an outpouring of remembrance and fervent tales. For me, this extends three generations.

Later in my grandmother’s life her stories seemed to winnow down to the ones that really counted; one in particular that remained on heavy rotation was the time she and my grandfather ended up in a friends’ VW van in the 1960’s, outside Kitsbuhel, Austria sipping wine and swapping stories with Warren himself. For my father, it was seeing early Warren Miller movies at the Mountaineer’s Club in Seattle, with Warren in back, narrating the whole thing before his films featured a soundtrack. For me, it was watching his movies in the Sun Valley Theater over spring break, and the incredible energy in this small and ill-lit space.

For more than seventy years, Warren Miller has lived a “Don Quixote” life, as he describes it, from struggling to snowplow down a San Gabriel foothill in pre-war Southern California, to skiing with heads of state at The Yellowstone Club generations later.

Having sold his film company a number of years ago to his son, and in turn to a major media company, The Ski Journal was fortunate enough to meet Warren in his home this last year and sit down for a four-hour talk. Nestled overlooking a Puget Sound harbor, Warren and his wife Laurie are preparing to leave shortly for The Yellowstone Club tomorrow and their annual winter hiatus. While most 85-year olds are lucky to make it to the senior center for bingo, Warren excitedly talks about his most recent projects: his autobiography, a cartoon book on golf, his young entrepreneur Freedom Foundation and his latest crusade — to deliver ski and snowboard gear to a village in India where he has previously filmed. He leads upstairs to his study which holds his first camera, sailing trophies, drawings, manuscripts and a curious looking piece of metal and wood. A closer examination reveals a large saw blade cut into a narrower strip and attached to a wooden block with straps. “This is what the kids ski on over there,” Warren says, “it’s just amazing that these kids can pull from the things around them to make these skis. But imagine what they could do with decent equipment?” As such he has been working closely with K2 and others to compile used gear and ship this to the village.

A few weeks later, Warren would compress his vertebrae in a ski accident (his only real injury from skiing), but fortunately recover shortly thereafter to pick up a Lifetime Achievement award from the X-Dance film festival and get back to his writing. His continued energy and desire to work is infectious and inspiring.

While in the 1980’s, some of skiing’s too-cool-for-school industry types began to disdain the sunny disposition and standard formula of Warren’s success, his legacy has endured and today a new generation of skiers are discovering his body of work, albeit in some cases through attention drawn via a lawsuit filed by Warren Miller Entertainment (now owned by Bonnier Corp.) against Warren Miller the human being — a non-compete suit over his voice appearing in a film by Colorado upstarts Level 1 productions. While the byzantine legal machinations sort themselves out, one thing is abundantly clear, at the end of the day, Warren Miller is still the most influential living skier in North America, and perhaps the world.

Like the Johnny Cash of ski media, his classic works and timeless images still make generations of skiers want to ski. And nothing speaks to his contributions more than this.

As the metal gray skies vacillate between rain and snow and the tide starts to come in, Warren Miller reflects on his life, from a teardrop trailer near an irrigation ditch in Idaho to Academy Award nominations: It’s all about the freedom.

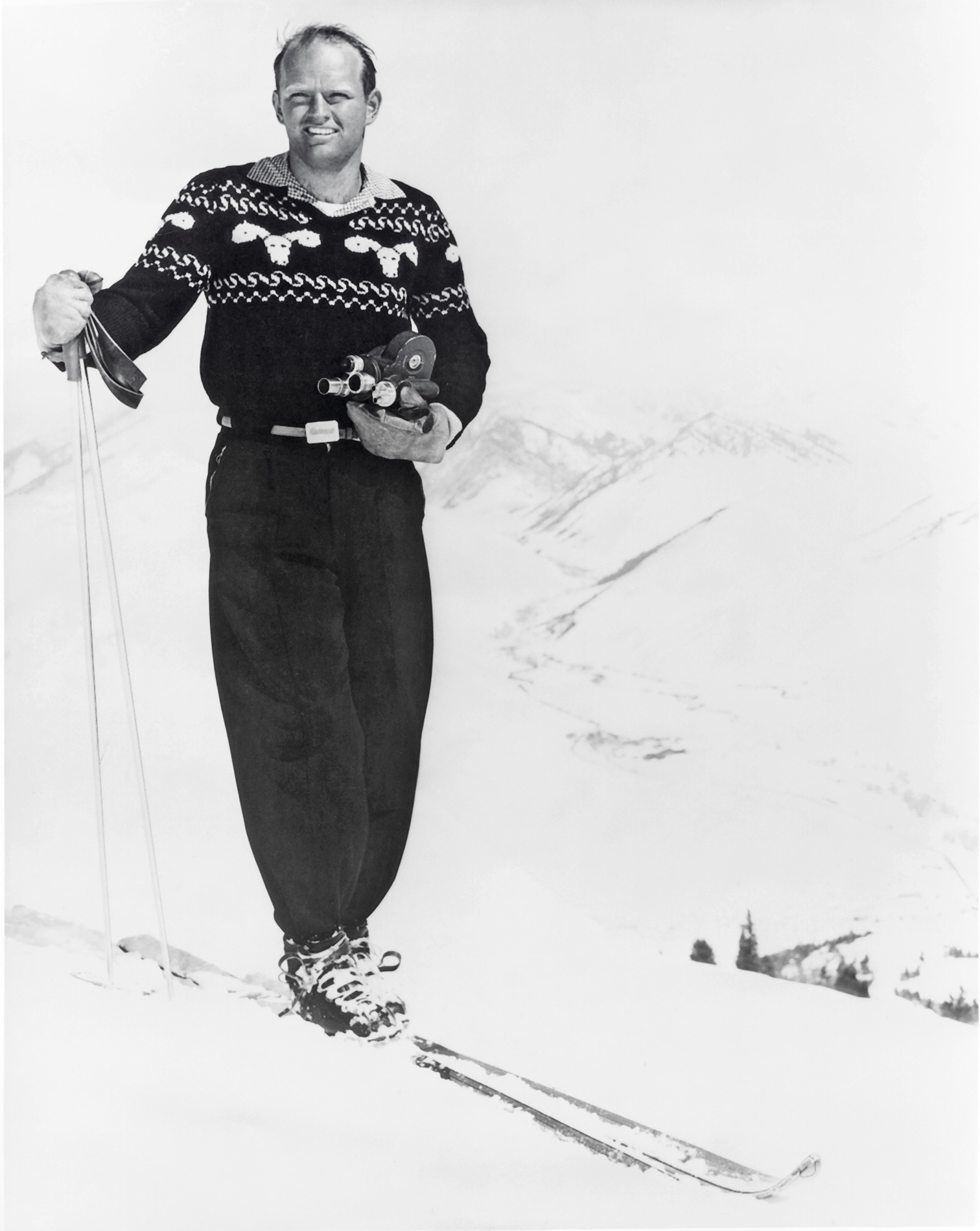

above Warren posing for the camera high atop Baldy at Sun Valley, ID, 1951, with his prized Bell and Howell film camera.

Strapping down Jean Claude Killy like a Dead Deer

I spent the most of last week working on my autobiography. I started it out with being rained on for thirteen days in New Zealand; a volcano blew up while we were over there. I hired a helicopter and we skied the Tasman Glacier. There were four of us on the helicopter, but only room for two. The pilot said “I can take two of you now and come back for the other two, but I won’t be able to find you in the dark, and you would die overnight.” Then he said, “Two can ride inside and the other two can ride on the outside.” Since I owned the company, I figured I they could ride on the outside. We tied the skis and the two athletes [one of whom was Jean Claude Killy] to the landing gear like dead deer. We gave them the option of riding face-up or face-down. They opted for face down in case they threw up. It is almost pitch dark, and because of the weight, the only way to fly off is to hop-hop-hop off the glacier and free fall until catching rotation and lift. This is the start of the book.

Since I owned the company, I figured they could ride on the outside. We tied the skis and the two athletes to the landing gear like dead deer. We gave them the option of riding face-up or face-down.

above The first speed flyer, Jeff Jobe embarks on the first-ever hang-glider flight off a mountain on skis at Sun Valley, Idaho, in 1969.

Seven Dollar Surfboards and Two-Dollar Skis

I was born in Hollywood. ..1924. Most of the life I led in Southern California I was on the beach. Started surfing early on; bought my first surf board in 1937. I was very lucky because I was 17 when they bombed Pearl Harbor, so I had a full year before I had to register for the draft. I got to surf pretty energetically that winter. It was just a question of getting gas because you got one coupon a week for five gallons. I’d give guys a ride to the beach and then we had 10 gallons to get home. That year and next I was really lucky because I had twelve days in Malibu when I was the only person in the water. Imagine that. And the water was crystal clear.

In those days the boards were so slow they couldn’t ride the North Shore. That is one of the reasons that Malibu was so attractive, the boards would work there if you had the right shape. I was lucky because I bought a Bud Morrison board for seven dollars. I bought it from some guy who had stolen it; turned out Bud recognized it, but he didn’t want it back.

The first time I went skiing, it was in 1937 up a dirt road from Mt. Wilson [Southern California], beyond Newcomb’s Ranch. We found snow beside the road on Mt. Waterman. My Boy Scout patrol leader had driven me up. He had gone to Yosemite over Christmas and had regular skis and bindings and I had a two-dollar pair of Spalding pine skis with toe straps and hiking boots with a leather pocket on the side…you remember? No, you don’t remember those. They used to have a pocket on the side and you carried a pocketknife in the pocket in case you got bit by a snake. So I had my high-top leather boots, with my pajamas on under my Levis…and obviously toe straps make it impossible to make a turn… the first time I tried to get into a snowplow, my feet went out and skis went straight and I tried that all day long. Finally I almost got to the fall line by the end of the day.

I probably climbed up that hill eight or nine hundred times that day. It was a patch of corn snow alongside the road. The uphill side of what was then a dirt road.

above Warren grew up surfing California’s beaches and, when he began making films, didn’t leave the sport behind. Here, he is pictured working on his first surfing movie in San Onofre, Calif., circa 1950, with his original waterproof box housing a 16mm film camera. (bottom) Warren and son Kurt in front of their Hermosa Beach, Calif. home in 1946.

You’re In the Navy Now

I went into the Navy in ’42. With the help of a friend I investigated all the Navy programs I could and officer’s training looked like the best deal. If you remember, I didn’t have to register for a year after Pearl Harbor. I registered in October of ’42. By that time all of the midshipman schools were chockfull. There was a program where you could go to college while you were waiting for midshipman school. Well, I waited at USC for a full year, got three semesters of college in a Navy uniform going to USC, eight or ten miles from where I was born. You would get up in the morning for exercises or breakfast and look up at the San Gabriel Mountains before the invention of smog and you could see the snow on Mt. Wilson.

So, I went to USC for a year, and then they transferred me to New Jersey. I was in a holding pattern. Then I went to Chicago for a few months. This was the formal part of getting my commission. I got good grades in midshipmen school and in college because I really didn’t want to flunk out, but once I got my commission, all I did was play basketball instead of studying. When they shipped me to San Francisco, we had to wait for transportation to the ship I had requested. Nobody wanted to be on them: 110 feet long, 27 people, made out of wood.

Got to Guadalcanal, was there for awhile, then they shipped us to Pearl Harbor, and, en route, we got sunk in a hurricane. Then back to Pearl Harbor. Between getting sunk and getting back to Guadalcanal for port of inquiry [Port of Entry?], they dropped the big bomb and we didn’t have to go invade Japan. With the Japanese invasion there would have been half-a-million people lost, I knew I would have been one of them.

That’s when I came back and bought my camera and house trailer. I got out of the Navy in June of ’46 and then that fall I tried to go back to college, but it didn’t click. In a class for 30 people, there would be 45…people sitting on the floors. I remember going to my geology class and standing outside to listen to the lecture through the window. I thought “you know, this is crazy’. That’s when I bought my house trailer and teamed up with Ward Baker and we left before Thanksgiving; arrived in Sun Valley in January of ’47.

above Warren and Ward Baker in Yosemite, April 1947, after completing a six-month ski trip while living in the pictured teardrop housetrailer.

Sun Valley Serenade: Free on Saturdays

Do you know where the post office is, in Sun Valley? It was meant to be within walking distance of the skier chalet. This is the Challenger Inn, post office… the lodge is over here…right? There is a road that goes like this up to the garage. Over here there is an irrigation ditch and a stand of trees. We just tucked right in here under the stand of trees. We had a Coleman in the back, gasoline stove…the trailer was a refrigerator; we didn’t need one of those.

The general manager, Pappy Rogers, was arguably the best PR guy I’ve ever met. He considered Ward Baker and me local color and so, I can’t verify this, but I know he told local operations to let us ride the lifts…and they did. He let us park our car there for two years…two winters. We got to ride the lifts; the only thing that controlled us was the snow conditions. When we woke up in the morning and it was snowing we were out of the trailer, so that we could be the first ones on the lifts skiing powder… and there weren’t half-dozen people in Sun Valley going in the powder at that time.

Lift tickets were four dollars a day. Season pass was $250. Wages for instructors were $125 a month plus a place to live. There were several things that were occurring at Sun Valley in that time frame, a ski train from Los Angeles arrived every Saturday and Saturday was check-out day, so there was nobody on the hill. There was a time when ski lifts in Sun Valley were free on Saturday.

That first year when I was at Sun Valley, I went to a dinner party at Trail Creek one night with some guys in my class. Some guy had shown a really crappy ski movie that night, and when we were riding home in a sled I was criticizing the movie. One of the guys said “it sounds like you know what you are talking about” and I told him I was going into the travel lecture business someday. He said, “Why don’t you go now” and I told him I didn’t have enough money to buy the camera I wanted. They asked what kind of camera I needed. In those days there were 50-100 guys making a good living, because there was no color television; they would go to Egypt and make a movie and show it in the winter and the next year they would go to Norway and make another one and then go back to the same circuit. It seemed like a pretty good life to me. I told them I wanted a Bell and Howell 70 DA with a wide-angle, normal and a telephoto lens.

Finally the guy said “you know I am really glad you like the Bell and Howell camera because I am the president of the company.” It was Chuck Percy, who went on to become a U.S Senator of Illinois and his controller Howell Jeanine. The next day in class, Howell came back from lunch and said “Chuck and I had a talk at lunch and we are going to loan you a camera and you can pay us when you get the money.” I didn’t even know what the president of a company did, much less ever meeting one. This was my first year of teaching, and so anyway, three weeks later the camera arrived in a leather box with red velvet lining. I probably slept with that thing for the first three months.

When I was first talking with them, I said “A camera costs $256. That is two months wages for me…almost two.” It was really hard to get ahead and that is why they sent it. But I paid them three years later.

So anyway, three weeks later, the camera arrived in a leather box with red velvet lining. I probably slept with that thing for the first three months.

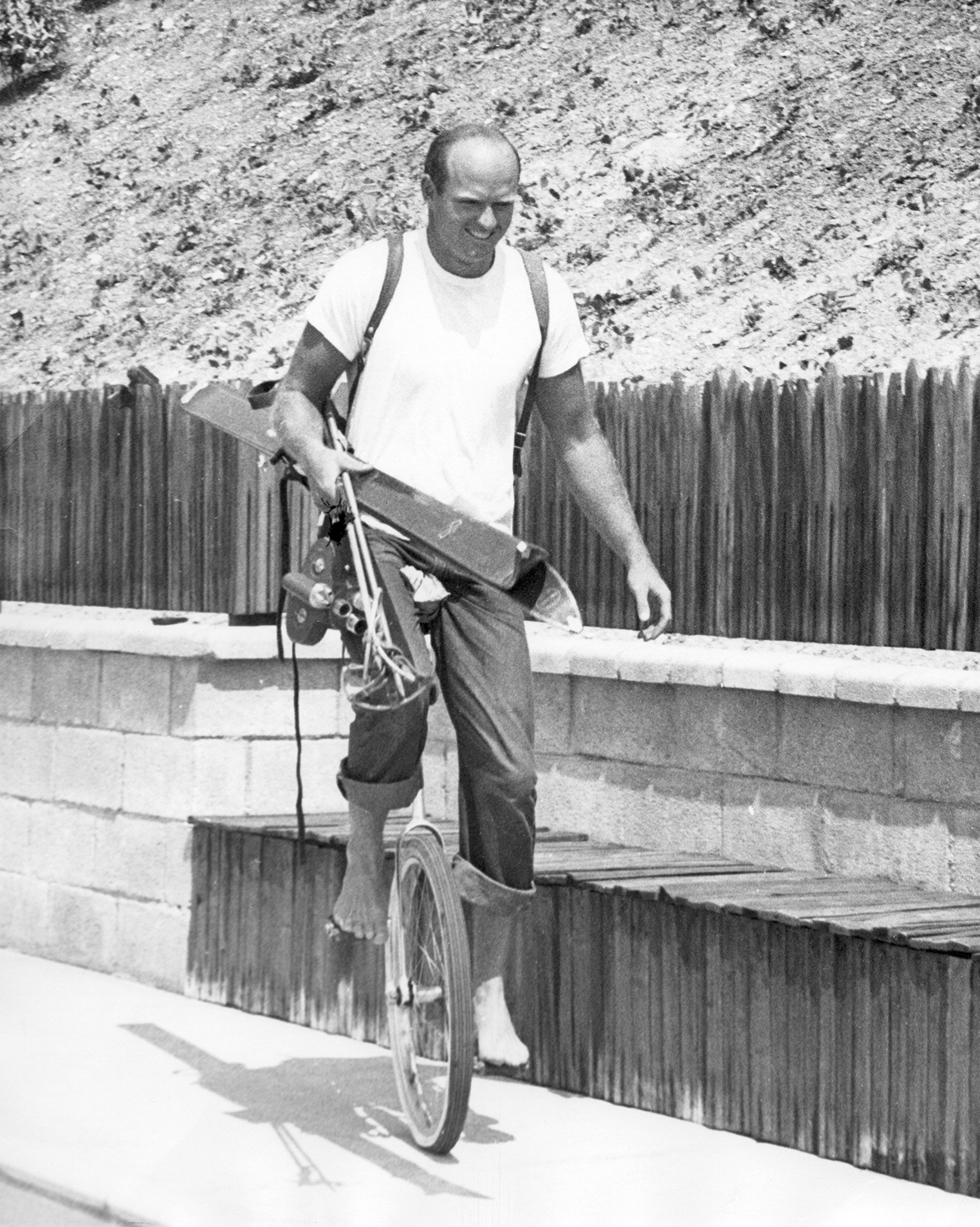

above Leaving the beach to start another ski movie in the fall of 1954 in Palos Verdes, Calif.

twenty Chairlifts in North America and a $400 Film

The next winter, when I taught at Squaw Valley, I was getting $125 a month. Those were the going wages and there were hundreds of guys standing in line for the job. The first year they opened was 1949/1950. I went there in the Thanksgiving of ’49. The valley slept 38-40 people and that was it.

I used to take still photos on my lunch hour of people eating lunch and then print 8x10s at night – all black-and-white — and then I would see the people the next day and try to sell them a photo of their vacation at Squaw Valley for one dollar. Well, if I sold ten of those, I could buy another roll of film. And if the guy was sitting on the porch with his girlfriend, not his wife, the picture was slightly different in price.

In Squaw Valley, every cent I got my hands on went towards another roll of film. They were ten dollars. By spring, I was able to buy and shoot 37 rolls, which is the length of a fully edited feature ski film, an hour–and-a-half. In the meantime when the snow melted, I bought a delivery truck to live in with a stove, and a bed, and a refrigerator. I had no overhead during that summer. I was digging ditches and pounding nails and editing the film. When I got the film edited, I needed $400 to buy a print of the film and a projector to show it. I couldn’t borrow $400 from anybody I knew. I didn’t know anyone that rich. Finally one day on the beach, some guys were talking and sipping, and I was telling them my tale. They were all very successful businessmen I found out later and they said “hey, why don’t the four of us loan you $100 buck a piece.” I said “great” and that I would go with it. They loaned me the $400, got the print, got the projector, and then I scrambled on to Southern California, showing the film to ski clubs trying to get them to sponsor the movie. The first nine or ten ski clubs I showed it to all had the same reaction. They liked the music, pictures were great, if you get somebody else to narrate it, and we will put you on. Finally I got a ski club that said “we will go with your voice.” And that ski club sponsored it for the next eighteen years: The Ski Club Alpine, in Los Angeles.

They finally got it in at the Santa Monica Civic one weekend we showed it, let’s see, Thursday, Friday, two shows on Saturday, and two shows on Sunday. There is an exhibition hall there also, so they had 46 different booths, like a ski show thing, and so after their success, I was thought it is kind of silly of me to be giving them 60 percent of this gross. That is when the company itself started doing the occasional show. I stayed with the sponsorship program the whole time I owned the company and there was no need to change it. I had a $200 guarantee of 40 percent of the gross. So they rented a high school auditorium for $50-100, then I supplied them all the advertising material, all the posters, postcards, the things they needed. There was a fifteen-minute preview that they could take around and show to other ski clubs. I tried to make it as turnkey as possible for them.

The hard thing to remember is that when I started there were less than 15 chairlifts in North America. There was one in Washington at Mt. Spokane, one in Oregon at Timberline, three in California at Sugarbowl, Squaw Valley, and Mt. Waterman, three in Utah with two at Alta and one at Snowbasin, and Sun Valley was running four full-time…Colorado had two chairlifts when I started, both in Aspen, and then you had to go to Boyne Mountain, Montreal, and then New England. When everyone you know skis, you think everybody does, because everyone you know does…you hang out with them. You aren’t having oatmeal in the bowling alley with non-skiers. I was really lucky because at Ski Club Alpine, the first time we showed the film, in Pasadena, they sold over 800 tickets, close to 800 bucks, so I made $320 the first time I ever showed a film; I grossed $320, which almost paid for my raw stock to make the movie. The first one was at John Marshall High School in Pasadena. Tickets were a dollar plus tax.

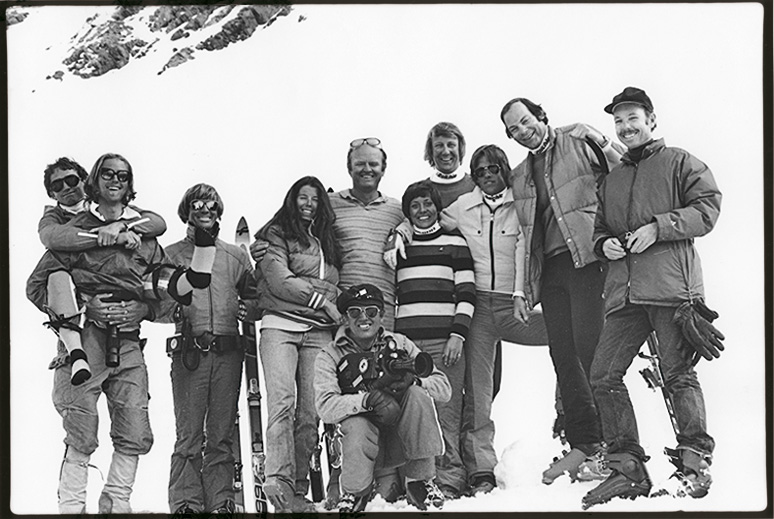

above On the set of Stein, Stork and the Chick

at Alta, Utah, 1975.

102 Cities in One Year: “Tell me how this works?”

I didn’t put sound on the film for the first ten or twelve years. I just had a tape deck and did every show live, aired it live, and played a musical background. The re-projector ran at a different RPM depending on how many hours it had. I had centrifugal circuit breakers and as the thing revolved it would get to a certain speed and the circuit would break and slow back down. Well, these points would oxidize and get lighter, so that it would be 25 or 25 and ¼ frames instead of 24, so it always took the first five minutes of the show to figure out whether the projector was going to be running fast or slow. So I played music and carried the show and then the business just kept sky rocketing and I couldn’t get to all the cities. I did 102 cities one year.

That summer I just went to a company called City Sound in Hollywood and said “tell me how this works” and they did. So I went up and narrated the film. In those days I didn’t write a script. It was all in my head. They ran the film for me in their studio. I just narrated live and we laid the soundtrack on the film. Put the music on the thing and I would rent the film for fifty dollars less. I was pretty booked up for the whole season, so anybody else that wanted the show got it fifty dollars cheaper. I couldn’t satisfy the demand. It was 1964 before I hired my first camera man. Before that I did the filming, music, editing, all the booking, all the contracts, all the advertising. Then in the fall I took my tape deck and film in a suitcase and hit the road until I came home for Christmas and took the family to Sun Valley. I could go there and show the film two or three times, get a new sequence for next year’s film, and they always took care of me…gave me a hotel over Christmas. It worked out very well.

In those days, there were a half-dozen of us making ski movies. Everyone wanted to be the first guy in town. After a few years of that, obviously I couldn’t be the first guy in Seattle every year, so it was a question of getting good sponsor commitments and they would reserve the theatre.

I remember one year the title of Jim Clineworth’s [early ski filmmaker] film was almost identical to mine. He wrote me a nasty letter saying that I was a spin-off of him, so I said why don’t you send me the name of your film and so I can make sure we don’t have the same name next year? So every summer when he decided on the name of his film, I would decide on almost the same name and say “Gee, sorry, I already have all my posters printed.” I did that for about four of five years. He finally gave up and drove a cab in Boston.

There is no reason why a film has to cost $100,000 or more.

above Danger on the glacier at Mike Wiegele’s HeliSkiing in Blue River, BC in the mid-‘70s.

If you can Turn, you are Extreme

In those days anyone who could make a half-dozen turns without falling was an extreme skier. Every place that I went in those days, the ski school director was the best skier on the mountain. So my sales pitch to management was “why don’t you let Siegfried and Freudal-Oopy-Doopy ski for me for the day and I will show him to 23 cities next winter and all those people will come flocking…” So the early years it was always the ski school director or the head of ski patrol. The second year I had a bit of a reputation, so that when I went back to those places, guys were already starting to want to be in the movies. Almost up until I sold the company, I think only two years I paid to take skiers to Europe with me. I did that for very instinctive reasons. Let’s say that you are a really hot skier at Mt. Baker and you have supported your habit by loading lifts, and let’s assume that for many you are the very best skier on the hill, and if I showed up with three bohunks from K2, Rossignol, and Volkl, imported to Mt. Baker, you will say “well, I am as good as those guys.” So now, you aren’t going to save those little stashes for me, you aren’t going to let me on the lift 30 minutes early, and so on. Getting access to those things really worked for me and it’s something that when my son bought the company I tried to explain to him, and also when the other people bought it.

There is no reason why a film has to cost $100,000. The first two times I used a helicopter, I didn’t have to pay for it because I had gotten a phone call from Alpental and Alpine Meadows, and they wanted me to come up, shoot some film and make a dog-and-pony show…this was sometime in the 60s. They supplied the helicopter. At Alpental, the first time they showed it, they showed it twice in one day, once in Tacoma and once in Seattle — they sold 72 vacant lots.

But I am not going to sit here and criticize any movies that the other guys are making now. They are doing a marvelous job of making movies. Whoever the audience is today, they jam six people in a car and park at Snoqualamie Pass and ride the lifts and that’s all they can afford. They can’t afford Valdez, but the films bring it to them.

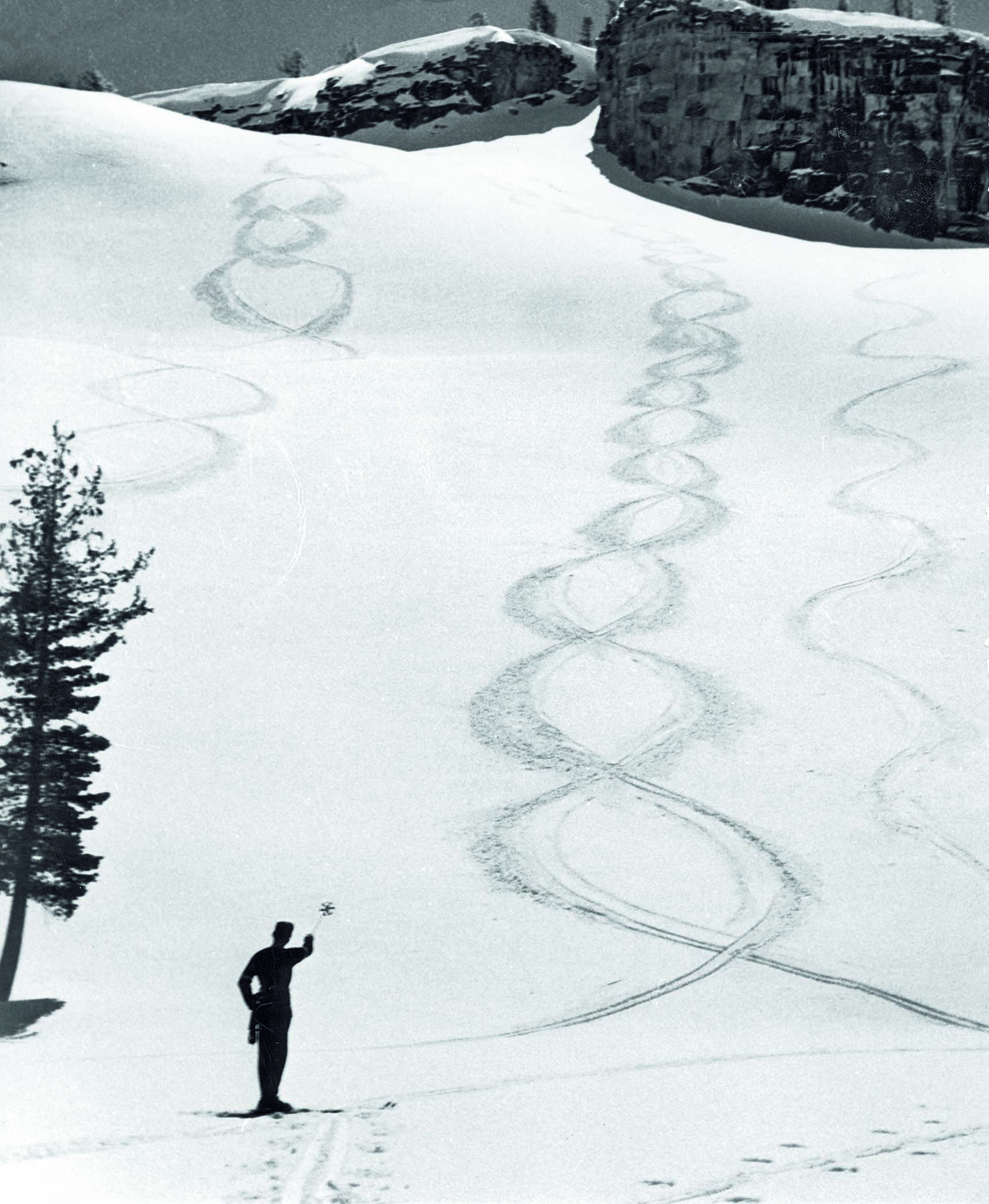

above Ward Baker and Warren leaving figure 8s on Horse Ridge at Ostrander Lake at Yosemite, Calif. in 1947, during their season-long road trip.

Racing and Europe

I went to Europe the second or third year I was in the business and my eyes were instantly opened over there. In the 50’s all the skiing in Europe was on south facing slopes because the resorts were all built around former tuberculosis sanitariums. They sent people up to altitude for the pure air; they got up out of the cold, latent smog of the valleys. When it came time to build a lift, they built them up a winding, south-facing slope and then you skied down the back. It wasn’t until sometime in the 60’s that St. Moritz went to the north side of the valley, but having the European flavor in the film, the destinations and the mountains, was – and I didn’t do any big analysis of this — it just seemed like the thing to do. This little kid that grew up in Hollywood has a chance to go and ski in Zurs, Austria with Herbert [Scheinder?] Pretty special. I always included shots of the hotels and the lifts and the schtick that went with it, so that somebody in the audience could hold his girlfriend’s or his wife’s hand and say, “maybe someday we can get on a ski charter flight to Europe” and trigger that emotional “I want to go there” stuff.

Racing in the films…one racer looks exactly like the next. I gave up filming ski races when Buddy Werner was killed. Because ABC or somebody did well at Squaw Valley with the Olympics in 1960, it became the big deal on T.V. But did I want to go with a film of the Olympics when it had already been on television? Didn’t make sense to me. Plus, they wanted an exorbitant amount of money for the rights. Should I pay $10,000 to film your ski race or should I just put that into the whole movie? I decided to put it into the movie. I just drifted away from it.

I came to the conclusion that the real heroes were the mountains themselves. There is an analogy here with mountains and golf. When I taught my friend Tom Wisecoff to ski, he said of golf, “Why bother keeping score? No matter how long you play golf the course will win every time.” Same thing with the mountains.

above Not too close to the gates, Warren displays “some semblance of the racing form” of the 1950s. Sun Valley, Idaho.

NXNW

I think a lot of the Northwestern influence on the early films had to do with the cooperation of the guys at Snoqualmie, Alpental and Crystal…they were very nice to me and they have great terrain. My wife had a ski school at Snoqualmie Pass, and the place is really a kindergarten of skiing. And Crystal is truly an awesome mountain… great scenery in the background of every shot.

All told, I have done 92 half-hour films on a variety of subjects. I made them about how to make wine, how to go to France…New Zealand, a lot of tourist films, made one for Micronesia Airlines, the French government, made one on sailboats. A lot of that started out so that I could use my sailboat as a tax deduction, the J 24 took us all the way to the world championships in Australia. Going into the finals with 96 racers, my kid driving, we three-way tied for first and ended up third. In ’62 I bought my first catamaran, followed by several other boats over the years.

The first summer we [Warren and wife Laurie] came up here, she was going on a bicycle trip. We got on the Anacortes ferry; sailboats in the background, stunning views of Mt. Baker and I thought: “Holy smokes, I have died and gone to heaven.” The next summer I brought my camera boat up here, finished my film, we cruised in the twenty-foot boat with a Coleman stove and a port-a-potty. We cruised up here for three weeks in the San Juan Islands. In our third year we were in that boat for six weeks, four-hundred miles north.

That winter, I tore my rotator cuff in Aspen — we were living in Vail at the time. I said, “We have never seen any of these islands from the beach, why don’t we drive up there and see what it looks like.” We were on Orcas Island, I wanted to write a script for a movie, we rented a condo, and my wife searched out real estate agents. One thing led to another. We had looked at almost everything that was on the island for sale and we were staying with a lot of friends. Someone said there is an old burn-out foundation that you guys should look at. The house had burnt down in 1954 and no one had been there since then. We hung out and walked down to the point decided that we wanted to buy the place. We were only there for 30 minutes.

I think a lot of the Northwestern influence on the early films had to do with the cooperation of the guys at Snoqualmie, Alpental and Crystal (Mountain)…they were very nice to me and they have great terrain.

aboveOn location in the Canadian Rockies, circa late-1970s, three unidentified skiers make turns while the cameras roll.

“I Don’t Really Do Surprises.”

I never had any corporate sponsors for the film itself. I would sell a page of advertising in my giveaway program. Since they were advertising in the program they might as well send me half-dozen parkas to put on the skiers. I think the biggest commitment I ever got was a round-the-world ticket with Pan America one year. We went to Japan (that was the dumbest thing I ever did) and to India, and to Switzerland.

Laurie and I were in Maui for the summer and I came back for a production meeting and one of the guys [from the Hollywood company who had purchased half of Warren Miller Entertainment at that time] said, we want you to save the first week of September because we have a surprise for you. I told them that “I don’t really do surprises.” With a straight face, the guy who was running the film company said, “We have two hotel rooms in Carmel and the best voice coach in the country to work with you.” I told them that I would think about it and get back to them. Soon thereafter our five year contract was up and based on their lack of knowledge on what the success of the company was really founded on — which was my storytelling — if I thought after five years, that this was all they really understood? I decided that I didn’t want to work with them. That is when I sold my half to [son] Kurt and he bought their half.

While we are on the subject of Hollywood movies, I have a couple shorts that were finalists for Academy Awards (one was on horse racing and the other one was titled “Freeride” [a multi-sport film]). I had a friend that was an Academy Award animator and he tried for years to get me into the motion picture academy. I was never allowed. We skied together in Sun Valley for years and I would always say “Try again; let’s try again.” He told me the problem, “Warren they don’t think you make “real” movies; which I don’t.

I don’t have the lights, don’t have 23 employees, and I don’t belong to the union. You know the whole time I was making movies, only once was there a union issue with a skier. I was filming at Timberline Lodge and we had been climbing and jumping crevasses…we broke for lunch and the guy said, “How are we going to keep track of my residuals?” I said, “I don’t know, how do you usually do it?” He said, “I belong to the Screen Actors Guild and I am entitled to them.” I responded, “Okay, would you like another sandwich?” He said, “No, I am serious.” I said, so am I: I’ve never gotten residuals for any film I’ve ever made. I believe in charging a fair market price for the time and talent at that point in my career. I treat the people that work for me the same way I would treat a plumber. If I pay a plumber to fix my toilet for me, I am not going to pay him every time I flush it. I told him, “If you don’t want to go back on the hill after lunch, get to the hotel, check out, and get to the airport the best you can.” He opted to keep skiing.

above On top of Durrance Mountain filming a four-season film for Bill Janss, owner of Sun Valley during the early 1970s.

Because if you don’t do it this Year…

Right now I’ve got a cartoon book almost 85 percent finished; it is getting a little traction already. I spent two-and-a-half years writing a book about aging. The working title is: “How Old Would You Be If You Didn’t Know When You Were Born?” I also self-published nine personal memoirs when I was in the Navy… around 1943.

My favorite movie is the next one I make…there were so many high points while I was making them. A lot of that stuff will get be in my biography. From 1950 to now, 65 years or something, that is a long time; I can’t even remember the titles to all of them, much less who was in them. I have 20-30 scripts up there still, some of which aren’t even in print. They are just all in my brain.

I really think that when you make your first traverse across a hill, it’s a person’s first real taste of freedom because the only thing that is controlling his freedom is his own adrenaline.

above Doug Pfeiffer performing a tip roll in the mid-1950s in Squaw Valley, Calif. Pfeiffer, a Canadian, moved to Squaw Valley in 1950 to apprentice as a ski instructor and served as the head of the ski school at Snow Summit, Calif., from 1953-63. He then became editor of Skiing Magazine and was behind the genesis of competitive freestyle skiing in the early ‘70s, among other contributions to the sport. He is now a member of both the U.S. and Canadian Ski Hall of Fame and remains active in the world of ski media.

Icons

Hannes Schnieder

Hannes was a wonderful person and incredible skier. I was filming a movie “The Harriman Cup” in 1951 in the spring in Sun Valley and had a chance to film him. He would have been in his sixties at that time. I was going through some notes recently and I found one from Hannes apologizing for “being in such bad shape at the time, and turning so poorly.” And of course his skiing, his turns, were fantastic.

Scot Schmidt

We found Scot in Squaw Valley. Gary Nate was filming at Squaw Valley and sent all his footage back. One shot really tweaked my imagination; Scot Schmidt was skiing and made a left hand turn, dropped off about a 60-70 foot cliff and kept on skiing through the powder. So we featured him that year and for the next four or five years. He came from Bridger Bowl and had come to Squaw Valley to become a ski racer. The steeps and freedom at Squaw Valley were much more attractive to him than running slalom gates while everyone else was skiing in the powder. We took him to Australia and Europe. We sent him to a lot of places. He appeared in the films for three or four, five years in a row.

Dick Barrymore

I had the longest running film career, and Dick had the next. Dick made feature films for 10-12 years, which is really quite long. Most are in it for three-to-five years and then you figure out that you can’t make any money doing it.

Bill Janss

In 1944, I met Bill Janss in Yosemite National Park, where he was the winter sports director; he had already done his tour of duty and he gave me my first ski lesson. We became really good friends and then he went through that tragedy where he almost lost both of his kids and his wife in that fire in Sherwood, he kind of disappeared for eight or nine years. When he bought Sun Valley we became reacquainted. I ended up making an all-seasons film for Bill; “Sun Valley: A Place for all Seasons.” The first time Bill showed it, he sold Elkhorn to John Mansville for what he’d paid for Sun Valley – the very first time through the projector. He ended up selling me 11 acres for a really good price. I subdivided it and did really well. He was an all-time giving human being; the only person that was better than him, was his wife and unfortunately she was killed in an avalanche. She almost lost her life previously in a fire, jumped out of the second floor window, found a ladder to go back and get her kids, she was pregnant at the time.

Bill got caught in the ’76 no-snow squeeze, there were some financial shenanigans that were going on that he had nothing to do with, but he really got ripped-off badly. The family is still very well regarded in that valley.

Dick Bass and Frank Wells

Dick Bass came to me in a round-about way. When Ted Johnson was rounding up mining claims in Little Cottonwood, he came to Southern California and we talked about it. Anyway, Barrymore shot an awful lot of footage for him (Ted) at Snowbird and that summer when he wanted to make a dog-and-pony show out of it he was too busy doing something else and he asked me if I would edit it. So, I put a dog-and-pony show together with Barrymore’s footage. This guy Frank Wells drove out for a meeting in Minneapolis which didn’t really raise any money. Somebody said that there is somebody down in Texas that really likes to ski and you should show it to him down there. So he drove down, met Dick Bass and showed him the movie. Dick was in the middle of a seven summit [summiting the highest peak on each continent, Dick Bass later published a book on the experience: “Seven Summits”] attempt with Frank Wells [who would go on to become President of Disney Corp] at the time.

I became a pretty personal friend of Frank’s. We skied together a lot at Vail; I skied with him every time he came to Vail. He always skied top-to-bottom without stopping. One spring he called me on a Monday and said he had a helicopter arranged and wanted me to come down for the weekend. I told him I would really like to, but Laurie and I were moving to Orcas that weekend and we already had it all planned. He said, “We’ll change it and go on Monday.” I told him “no” it is already all planned. He said, “Miller, you cheap S.O.B. Don’t you realize the weekend is on me. You don’t have to spend any money. You have to come and ski with us.” I told him, “Frank there is nothing more I would love than to come and ski with you because you are my best friend.” Monday I would have been on every run with Frank sitting on a helicopter with him. Lori and I were at our property on Tuesday, when I got a phone call and the voice said “My mother would like you to speak at my father’s funeral.”

I would have been sitting right next to him. He hit a tree going 125, right in front of the pilot’s face; went over a cliff and stopped in the snow.

Otto Lang

Otto became a very dear friend when I met Laurie. He was living in Southern CA at the time and we became very close the last 20 years of his life. When he was 80-something he wrote his autobiography; he said he did it for his children. He has been in the back of my mind the whole time I have been writing mine. He wrote it on yellow-lined paper with a ball-point pen. Wrote it when he was 90, it is a great read: “Around the World in 90 Years.”

Dick Durrance

I wrote the introduction to his book. He had 16 National Ski Championships under his belt, won the Harriman Cup three times, was National Junior Champion when he was nine or 10 years old. His mother and father sent him to military school in upstate New York; he said when he first saw snow he couldn’t believe his eyes. His mother showed up one day and said they were going to Europe, put him on a boat, and went to Germany and Austria. On the boat they found a brochure for Garmisch, so they went to Garmisch. He and his mother just went knocking on doors to look for a house, this was in ’33 I think, but when Hitler loomed on the horizon, they had to move back. He was so much better a skier than anyone else in America at that time. He really was the Jean Claude Killy of his day. I can’t say enough about him as a person. He was the first person in the Aspen Ski Corporation. He made movies for Boeing during the war and made a lot of prize-winning short films. He was a great filmer, he made the first ski film in Sun Valley.

Stein Eriksen

Probably the most influential guy of the ‘50s and ‘60s was Stein Eriksen. He came to Boyne Mountain and was paid more than anyone had ever been paid as ski school director. He skied in front of my camera that first year and about three years later I showed my film in Detroit and he got really angry. He said, “Warren, what you said in the movie wasn’t true.” What I had said was that he turns one way with rotation and the other way with his left shoulder. Every picture you see of Stein he is turning left like this. So, I got a projector and put it in the hotel room. He told me that all the years he skied, no coach had ever told him that. I don’t know how many girls bought stretch pants and skis hoping to get a ski lesson with Stein with not-necessarily-any-skiing.

above Stein Eriksen, fresh off a gold and silver in the giant slalom and slalom, respectively, at the ’52 Olympics in his home nation of Norway, came to Sun Valley, Idaho, before becoming ski-school director at Boyne Mountain. Warren calls him simply, “One of the most influential skiers of the ‘50s and ‘60s.”

The Real Ski Heroes

Tracy Taylor was probably the most talented young skier I ever filmed. We went to Southern California for a ski race, one of those big celebrity things. It was for the March of Dimes, the March of Dimes girl was a little girl named Tracy Taylor. About this tall, eleven years old, she was in a wheelchair, her legs were in casts. After everyone had their picture taken with her, I picked her up in my arms and found her mother. I asked her mother if I could take her up on the chairlift. We got on the chairlift and this girl gave me the best hug I have ever had in my life. I skied down with her in my arms; by the time I made my third, turn she was giving high fives to everybody. Got back on the lift and next time I skied down with her between my legs. Then we went through the race course and she was sticking her hands out to hit the poles. I called her a week later and told her mom I was making arrangements for her and her family to be flown to Winterpark to teach Tracy how to ski. When I called back her mother said that she was outside with her brothers running their Olympic luge course in her wheelchair. This gal has spirit. A camera man and sound man went along with Tracy to Winterpark. The sound man did a great job. Tracy says in this little tiny girl voice, “God made me this way so that when other people see me, they believe that they can do anything they want to do.”

We went to Snowmass, Colorado for the World Ski Championships. There was a guy there named Mike May, who blew his eyes out when he was three years old. He was completely blind and trying to break the world speed record on skis for a blind man. The insurance companies found out and told Snowmass that if Mike went through the start gate that their insurance would be cancelled. We had just driven so far to film Mike. I suggested that he just start his run from below the start gate, so that he wasn’t breaking any rules. He set the world record at 73 mph for a blind guy. He comes and ski with us, we were skiing on a run called Family Tree, then we went and had lunch, then in the afternoon we went back to Family Tree and he asked if he could go first. We skied top to bottom.

At the bottom of every ski run you ever make, you are a different person than you when you got off at the top. I don’t care who you are or what the snow conditions are like.

above On his first trip to Europe in the early 1950s, Warren traveled to St. Anton, Austria. The caption on the back of this photograph simply reads, “A blend of different ski techniques.”

No Spitting From the Lifts, No Loose Clothing, No Unsecured Ammo

I have really been lucky in meeting these truly inspirational people. At the Yellowstone Club one time, we shut the place down, and Benjamin Netanyahu, his wife, and his bodyguard showed up. For a few days at the club, we were the only ones skiing. One bodyguard was on a snowboard and the others were on skis. None of them were very good, but they all had years of army training and were very strong. One of the bodyguards got out of control and we were yelling at him to put weight on his left foot…it was kind of an out-of-control snowplow, which of course ended in a yard sale…poles, gloves, helmet, skis, and all the other stuff a guard would carry, handgun, bullets, etc…

above A trio of ladies pose at Mammoth Mountain, Calif., in June of 1958.

Level 1, Lawyers and Insanity

JG: With the whole Level 1 thing, what happened…?

WM: I narrated five little stories for their film, answered five questions, and the next thing I know the film company [WME] took offense to that…

JG: They went after the kids at Level 1 right?

WM: I think so.

JG: Level 1 interviewed you right; it wasn’t so much in the context of a narration?

WM: Exactly right. It was an interview. It was not different than what we are doing right now.

JG: That’s insane.

WM: You put the exact word on that: “insane.”

above Miller and Level 1’s Josh Berman on San Juan Island, 2009.

A Psychological Enema

I don’t understand why they won’t let these motor homes park at resorts. You know, six motor homes, well that’s 24 lift tickets, is my attitude. I have been doing a lot of Don Quixote things my whole life, I just believe in this freedom thing. I always tell young people moving to the mountain to get an electric blanket, go to a 7-11 and give the guy working a five dollar bill to plug in. If you have seven different places that you can plug in one night a week, well there you go. Its called entrepreneurship, which is why Laurie and Colin [son-in-law] started the Freedom Foundation about entrepreneurship, it’s all about being straight up honest.

When I talk to people about their first day on skis — and I could ramble on about this — if you learned to ski or snowboard after the age of five you can remember everything about that day. What time you got up, the clothes you wore, the socks you wore, where you went, what you had for lunch, who you met, what you did, everything about it. Can you remember anything else in that time frame that exactly? I really think that when you make your first traverse across a hill it’s man’s real first taste of freedom because the only thing that is controlling his freedom is his own adrenaline. If he’s got a lot of adrenaline going he will go a lot faster down the hill. Once a person completes a turn, the adrenaline really comes rushing out.

You know when you went skiing it changed your life forever. Did it change you for the worst? No. If you had been destined to become a criminal, you would have become one whether you skied or not. At the bottom of every ski run you ever make, you are a different person than you when you got off at the top. I don’t care who you are or what the snow conditions are like. I use a term that is not very polite, but it is a real psychological enema every time you ski down the hill. All the garbage in your brain kind of drips away and you’ve got to, whether subconsciously or not, focus on how wonderful that freedom that is and you can feel it in your body, your knees, your brain… your pocketbook…. Because earning enough money to enjoy that freedom is getting more and more difficult.

A season’s pass at Vail for $599 is a real bargain and some of the resorts are in the $1800-2000 range. An academic exercise for you would be to Google a travel agency, and figure out what it costs, let’s say you have a wife and two kids and you live in Connecticut… what is it going to cost you to get everyone to the airport in New York City, park your car for a week, fly to Denver, rent a four-wheel drive — you know $75 or $100 bucks a day, rent a two-bedroom condo, breakfast will cost you $50 a day, $75 or $100 for lunch, and certainly dinner is going to be more than that, your wife is going to buy a new ski outfit, and by the time you stand in long lines and say “screw this” and hire a private instructor for $874 a day, so that you can get on the lifts… Where do you stop? If you sit down with a pencil and paper and add it up, it is a shocking figure. At the same time there are a lot of people that live a two-day drive away, and four, five, or six people stay up all night driving in a van. That is the other side of the equation that I encourage. These other people are going to come, they are going to pursue skiing; I think the people who really need to pursue it, are the ones who don’t have a lot of freedom. I was really fortunate because I grew up with almost zero supervision and I had freedom my whole life. I was just really lucky.

above Warren having a laugh after filming yet another comedy sequence for one of his annual feature-length films in 1987; 40 years in and still loving it.

Board with the World

I raised my kids on the beach of Hermosa. When the kids started skateboarding, it was on bun boards, which were burnt-out pieces of wood on which the baker would cool buns. They were spray painted red, with metal wheels. When the kids couldn’t swim, they went skateboarding. The police would harass them, so they invented a whole generation of kids who were waving the finger at the police.

Later, I realized how much that freedom meant on a skateboard. I started raising money [for a skateboard park on Orcas Island] and about four years later I had raised $64,000. The superintendent of the school gave a piece of land. We started interviewing skate park contractors. I hired a contractor, Mark Hubbard, that was building a skate park in Eugene, but lived out of the back of his car – so I knew he was perfect for the job.

Within some time we raised a quarter-million dollars from people on the island for the remainder of the construction. People were coming from Bellingham, getting on the ferry at five in the morning to lay concrete. This reminded me of one of my favorite quotes, from Tom Watson (his father invented IBM), which I found on his refrigerator one time I stayed with him: “There is no limit to the amount of good a person can do, if he doesn’t care who gets the credit.” We had that embedded in the wall of the park. The Kiwanis Club donated bleachers and put up a plaque saying they had donated them, so we took that plaque down. Nobody was getting any credit for the park. It was a place for kids on the island to go and be free; the only stipulation is that they have to wear a helmet.

Shaped Skis

It changed things very dramatically. If they still made skis the way they did in the fifties, less than one fourth of the people doing it today would do it. Go to the Salvation Army, get some of that old equipment, go up to Mt. Baker and put them on some of the guys that are really good…they won’t be able to make a turn on the bunny hill. They just won’t turn.

I don’t understand why people continued to ski; you know, their boots were soft, skis were long and stiff, the clothes were cold…

Go to the Salvation Army, get some of that old equipment, go up to Mt. Baker, and put them on some of the guys that are really good.they won’t be able to make a turn on the bunny hill. They just won’t turn.

ABOVE Jumping on straw at Mt. Baldy, Calif. in July allowed a comfortable clime for the bikini-clad lady in this 1965 image.

Being Warren Miller

I get out of bed and cook a bowl of oatmeal, then I am already ahead for the day. I get out on the hill whenever it is sunny. I have macular degeneration of one eye, I got rid of my cataracts, and so this winter I may be able to ski more. I ski at The Yellowstone Club with people that own homes there, management; it’s full of a lot of successful business men. It fell on really hard times, but now is back on track. This winter, during Christmas vacation, there may be as many as three hundred people on those five quads and four doubles. Every run is groomed every night and when they groom the trails they only groom one side of them. I can get you untracked powder at four o’clock in the afternoon when there are three hundred people there. They just groom one side of the trail, so if someone wants to ski the groomed or the powder and you don’t want to, you can ski right alongside them. I skied as many as eight fresh tracks on one run once. People always ask what celebrities go there. There ain’t no celebrities. There is nobody there to look at them. The celebrities go where the paparazzi go.

Cindy Crawford was there and her daughter came over to me. My daughter had given me a bunch of fake million dollar bills that I give to kids, so I gave her one. I told her, “You have helmet hair; doesn’t your mother do a better job taking care of you?” Her mother was standing there and the instructor said, “This is Cindy Crawford.” When we left, I turned around and asked, “Who the hell is Cindy Crawford?”

I have been there eleven years now and never worn a suit once while there.

We’re going to Montana this week. I have been doing a lot of writing and enjoying it. It is a lot of lifestyle stuff, experiences I have had… There is no finish to it, because I am not dead yet.

above Warren at home in the Pacific Northwest, with his original Bell and Howell. Photo: Grant Gunderson

This article originally appeared in The Ski Journal Volume 4 Issue 2.