Culture

A Cut Above

The Angry Beavers Build New Lanes in Maine

First published in Issue 17.4 of The Ski Journal.

The chainsaws were a dead giveaway.

Jim Carter, the new general manager at Black Mountain of Maine, wasn’t sure what he’d find as he wandered toward the woods of his Rumford, ME, ski area, but spotting the same green Tundra in his lot again—and in August no less—had set off alarm bells. Through thick summer heat, Carter hiked up from the base lodge in search of answers. Somewhere on the side of the mountain, they almost ran into him.

Jeff Marcoux and his father Gerry had spent the afternoon dreaming of winter. For the last few days, they’d thinned trees and cleared deadfall near an area known as the Woods Trail, slicing pathways that, once the snow fell, would transform into private powder stashes. It wasn’t a legal practice per say, but one they’d operated undetected for a few years now. Plus, the risk seemed worth the reward—that is, until they stepped out of the forest and right into Carter’s sight line, incriminating tools in tow.

top to bottom

Bryce Hanrahan sets the first boot pack of the day from the top of the triple chair toward the summit of Black Mountain, ME.

All signs point to Black Mountain of Maine in Rumford, ME.

Tools of the trade.

“Oh, we’re busted,” thought the younger Marcoux.

Clandestine glade-cutting had earned East Coast infamy not long before that fateful day in 2010. Authorities were cracking down on unlicensed trailblazing across New England, and just a few years earlier, two Vermont men had even been charged with felony mischief. Their crime? Carving out a 2,000-foot shot off the back of Big Jay in the Green Mountains. The Marcouxs knew cutting on Black’s private property could carry even steeper charges.

Carter, however, had other plans. “I told them to keep doing it,” he says.

Carter, a former automotive industry engineer, had worked virtually solo to keep his non-profit ski area afloat since he took it over in 2009. In the Marcoux family he saw not only an avenue to keep his ski hill well-maintained, but to expand into something else entirely. “I knew I didn’t have the manpower to do it,” he says looking back. “If they wanted to cut [trails], that’s free labor for me, and something I knew that people were going to enjoy.”

That day, what could have been a police blotter entry turned into one of skiing’s most unlikely alliances. Shortly after the encounter, Jeff and his father launched the Angry Beavers, a volunteer trail maintenance crew that, over more than a decade, has partnered with Black to transform 50 skiable acres into nearly 600, turning their western Maine ski hill into a natural skiing hotbed and making a glade network a community affair.

Bryce Hanrahan soaks in the sun as he turns down the Headwaters Glade on an elusive bluebird powder day in the Maine woods.

Jeff Marcoux’s life has been forged in wood. He grew up just down the street from Black in Dixfield, ME, a town whose majority was employed by the local Irving Forest Products sawmill. The surrounding area was once home to a handful of similar operations, tapping one of the nation’s largest natural conglomerations of white pine, yellow birch and maple. Jeff spent his childhood in the factory’s shadow, lending his dad a hand around the family farm. Over the years, Gerry taught the younger Marcoux how to sustainably maintain the land, choosing the right trees to trim and leaving hearty species behind, avoiding clear cutting to protect his land’s cyclical ecosystem. When Gerry upgraded to a small bandsaw sawmill, Jeff learned how to cut logs and limbs on site, soaking up his father’s decades of hands-on experience.

Even when Jeff pursued a career at the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard in New Hampshire, the forests, and the mountains they grew on, were never far off. Bored with icy on-piste skiing, he began to seek out the secretive community of woods skiers that operate on New England’s shadowy fringes. Through a growing network in New Hampshire, it didn’t take long for him to realize that some of the best East Coast skiing isn’t found, but made.

top to bottom

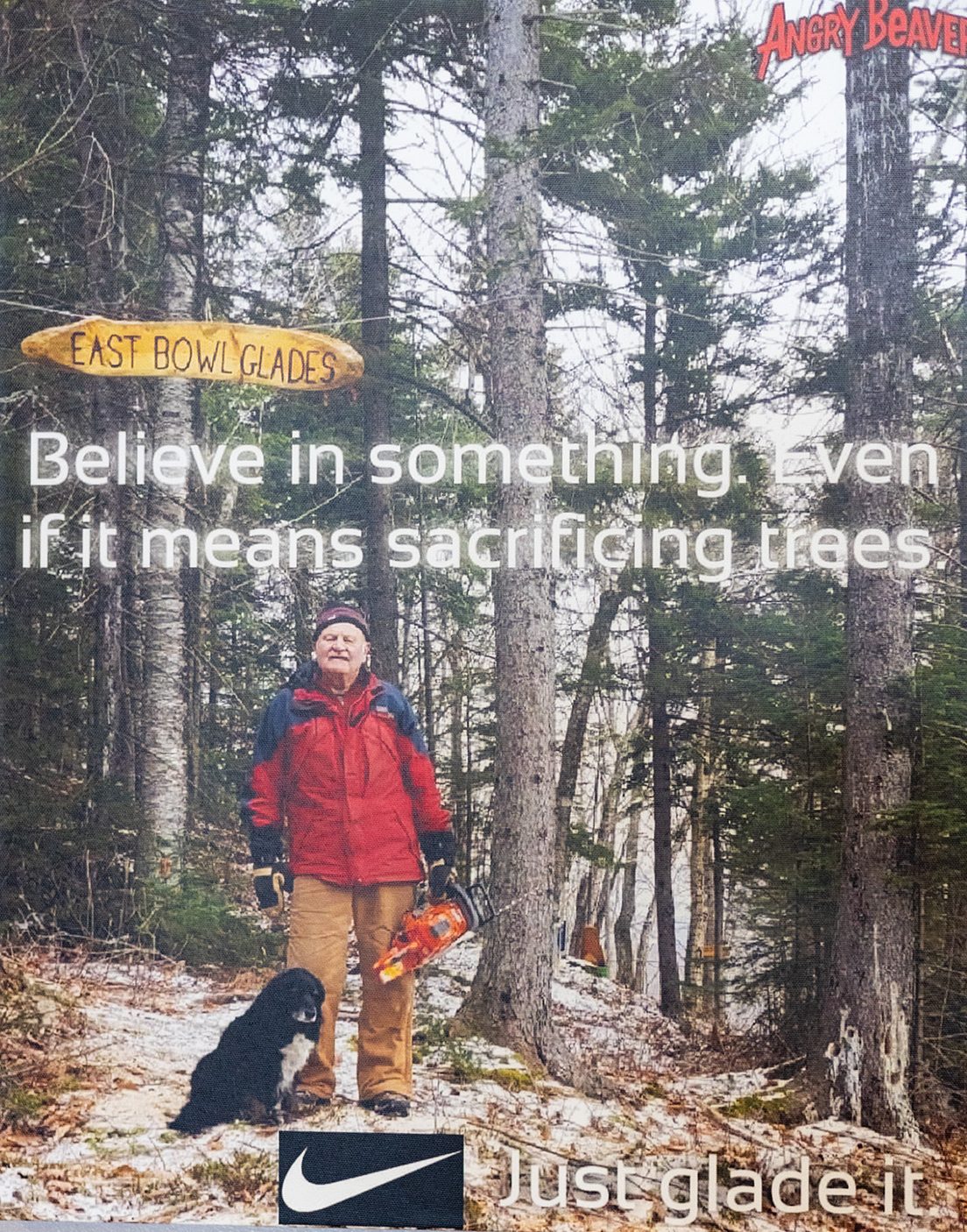

An inside joke among the glade cutting Angry Beavers turned into this “inspirational” poster featuring Gerry Marcoux and his dog Peanut, which still hangs proudly in the Black Mountain Base Lodge.

Michael Hogan, an original Angry Beaver, still takes to the woods every summer to help clear the way for his winter descents.

Once the snow starts flying, Jeff Marcoux trades in his brush saw for a pair of skis, complete with plenty of BMOM stickers.

Glade and backcountry trail cutting is nothing new in New England. When the government-funded Civilian Conservation Corps employed young men to carve trails off peaks like Vermont’s Mount Mansfield and Massachusetts’ Mount Greylock in the 1930s, they followed the natural contours of the land, keeping lanes tight to reduce environmental impact (and spice up the descent). As traditional ski resorts opted for wider slopes and larger capacities in the following decades, a disillusioned minority returned to those CCC principals, quietly sawing, clipping and trimming their own narrow passages to create a world of powder stashes under the nose of corporate ski America.

“There’s an intrigue to the adventure, in seeking snow where no one else is,” Jeff explains.

These hand-cut trails were often hidden out of necessity. More than a few people could ski out zones in a matter of minutes, with a single ski track entering thick woods enough to alert the lift-ticketed masses. As Jeff began to carve his own terrain in the early 2000s, he also inherited an oath of secrecy. He returned to Black in 2008, building trails with false entrances that led to brambly dead-ends, and often doubling back on his tracks to throw followers off his scent. Every time he entered the woods, he knew the stakes were high. “Once a stash is blown up,” he explains, “it’s never the same.”

top to bottom

The entrance to the East Bowl Glades, a playground of shots sitting skier’s left of the area’s summit triple chair.

In nearby Rumford, the local paper mill also deals with plenty of fallen trees, just on a much larger scale.

Yet standing in front of Carter on that August afternoon in 2010, chainsaw in hand, Jeff saw the future in a change of heart. “We had to go against the grain,” he says. With Carter and Black’s approval, Jeff could continue creating trails back at his home mountain, but they couldn’t just be for him anymore. “We had to make the woods accessible,” he explains. “I didn’t want to give up our fishing holes, but we wanted people to come [to Black] in order to keep the business going.”

Within a few short years, what had started as Jeff and Gerry grew into a band of over a dozen volunteers. They tied ribbons around trees in prospective ski zones during the winter, and returned in the summer and fall to cut trees, move deadfall and clear brush—anything that would optimize the ski routes come snowfall. They called themselves the Angry Beavers after the Nickelodeon cartoon, and, with Jeff at the helm, added handfuls of trails in those first years. After lobbying to Black’s volunteer board to create open boundaries in 2014, that number exploded.

“It just spiraled,” says Carter. “Suddenly we had a mountain made by volunteer labor. Today, we have well over 40 glades—it’s become a major part of our ski area.”

top to bottom

Nobody does vanity plates like Maine—not even Black Mountain’s parking lot is safe.

Ray Broomhall, a long-time Rumford resident, poses for a portrait with his first pair of skis, which are now on display upstairs in the Last Run Pub.

Yet with great expansion comes great responsibility. Before every season, Jeff meets with the board to explain his trail maintenance plan and then runs everything by ski patrol. In fact, it could reasonably be argued that there isn’t a slash on the mountain that hasn’t been run by the Beavers’ boss.

“Jeff is the mayor,” explains Lee McKay, a retired science teacher from Cape Elizabeth, ME, and one of Jeff’s go-to trailblazers. “Skiers are just coming up to him throughout the day telling him their cuts and where they might need bridges or work in the future.”

That kind of communication and flow is the name of the game at Black. Using the skills he learned thinning forests on the farm, Jeff has helped the Beavers establish a system for glading that lets the terrain shine. Volunteers ranging in age from early 20s to late 70s cut trees of any size, but make sure to leave gaps of six to 12 feet in between standing trunks for fluid and fast skiing. Entering East Bowl off Black’s main triple, the playground is easy to find. The Beavers grind stumps down to the ground and move deadfall to create ramps and rollers over rocks, so with just over a foot of snow, these zones are game on.

Hanrahan finds one of the many steep and deep pockets stashed away in the larger expanse of glades. Even later in the day, these pockets can still be untouched.

“We have some pretty technical stuff for a small, intermediate mountain,” Jeff says. “We have drops, 20-foot cliffs and hucks. When this place shines, it’s really something to see.”

Riding up the Summit Triple on a powder day, the evidence of the Beavers’ handiwork is often heard before it’s seen. Whoops and hollers reverberate across the hill as patrons of all ages dip into groves of hardwood, a phenomenon Jeff amusedly calls the “woo birds.”

Black’s trail map has had trouble keeping up with the amount of new glades appearing year after year. So too have the crowds, which is just fine by Jeff. “We’ve been able to make new offerings to outpace the interest,” he says, adding that if he sees a pair of tracks, he’ll probably head to a different trail and a fresh canvas.

top to bottom

Beaver Creek, CO, may be wondering why so many Mainers

keep visiting…

A symbolic rubber chicken hangs on the sign pointing towards the “chicken run” back to the lift. Plenty of good skiing remains below if you’re up for it.

This isn’t to say that the woods are empty. Word of Black’s glading experiment has spread throughout the Northeast, and Carter believes the Beavers have been major players in revitalizing his non-profit ski area. “Our name is getting out there,” says Carter. “The glade network has absolutely helped that, helped the growth of our mountain. It’s brought more skiers here, no question.”

The small ski hill has earned kudos from co-ops like Mad River Glen and has been added to the Indy Pass. It’s also caught the attention of the Granite Backcountry Alliance (GBA), a non-profit promoting and growing backcountry trail networks in New Hampshire and Eastern New England.

“Glades are overlooked as this thing that’s a given [at the ski resort],” says Andrew Drummond, a GBA board member and the owner of White Mountain Ski Company, a ski shop in Jackson, NH. “You don’t realize the work that goes into creating and maintaining them. That’s the coolest part about these glades—you know there’s caretakers that are going to get in there at some point.”

The view from above the iconic Black Mountain summit triple. During the winter months, “woo-birds” can often be heard hooting and hollering from the woods on either side.

In 2019, GBA partnered with the Beavers to unlock a new zone of backcountry terrain between Black and nearby White Cap Mountain, adding a series of 600 to 1,400-foot human-powered ski lines. Beavers volunteers built the uptrack from the parking lot, an effort spearheaded by McKay, and helped install a backcountry gate accessing the 8-mile point-to-point tour.

Over a few days this past summer, a dozen or so Beavers tidied up their vast maze of trails, teaming up to clear debris and cover potential hazards. Per Beaver guidelines, no wood was removed from the forest. Jeff says that with their exponential expansion, that’s become more of a job than a chore. Still, he, McKay and crew found time to make three more expert glades into East Bowl.

top to bottom

Walking the plank back toward the base lodge.

Keith Bobrowiecki, BMOM Director of Snowsports, keeps the vibe

fun for everyone.

Black’s cult success can be traced back to these long summer afternoons in the forest. Yet while the Beavers are proud of their place in that story, it’s the new trails that keep them coming back year after year—a chance to not just explore the woods, but to have their hard work paid back in powder turns.

“We build the glades we want to ski,” says McKay on an afternoon skin lap. “While you’re building it, you just envision skiing it. I’m invested in these glades. We know how to ski them because we helped build them.”

top to bottom

Gerry Marcoux wasn’t always a tree skier, but after starting to cut trails with his son, it was hard to resist the goods in the woods.

Jeff Marcoux leads the parade through the Rapid Glade. There’s

nothing quite like skiing the trail you cut, turn for turn.