Adventure

Michigan

Immense, Wild Joy: A Michigan Ski Reunion

First published in issue 17.1 of The Ski Journal.

Icy lake water presses the air from my lungs and I can’t get to the dock ladder fast enough. Robbie Koets had descended slowly in the January chill, forcing himself into a zen trance with only hands and head above the surface. He said this strategy allowed a thin bubble layer to form around his skin, offering some modicum of insulation. But my cannonball burst that bubble and shocked him from his reverie.The 50-degree air and gentle rain feel good as we emerge from the lake, but man it sucks for skiing.

“My wife (Colleen Dupuis) and my daughter (Lumi Bolen, 3 years old at the time) were the only crowd at Porcupine Mountains Ski Area, which lies within a state park near Ontonagon, MI. The lift overlooks Lake Superior and though really pleasant this day, it can be bitterly cold and windy.” Photo: Kyle Bolen

Bittersweet Ski Resort, the 350-vertical-foot hill I learned upon, had once been a 300-vertical-foot hill, but the sum- mer before my senior year of high school bulldozers added an extra cushion of earth for a new high-speed quad. Today, not one of those 350 feet is open in an attempt to conserve its meager snowpack. The mountain manager laughed at me this morning when I asked if we could hike a few laps, but I hadn’t been joking.

It was an inauspicious start to this Michigan ski road trip that my group of friends, close since our eighth-grade ski club days, had talked about for a long time. Though the responsibilities of jobs and kids had made the prospect more difficult with each passing winter, we’d carved out five days in which to ski our home state. When I left my eight- months-pregnant wife, Amy, for a snowy drive to the Salt Lake City airport earlier this morning, I hoped my own next big responsibility would hold off at least another week. We’d lost a ski day to unseasonably warm early-January south- west Michigan weather, but tomorrow we’d head north on a mission to find snow and ski some of the best slopes the Great Lakes State had to offer.

MY FRIENDS AND I SKI THESE SLOPES AS WE’D DONE MANY TIMES BEFORE, WITH NOBODY PARTICULARLY LEADING AND NOBODY FALLING BEHIND, TURNING LIKE A MURMURATION.

above top to bottom

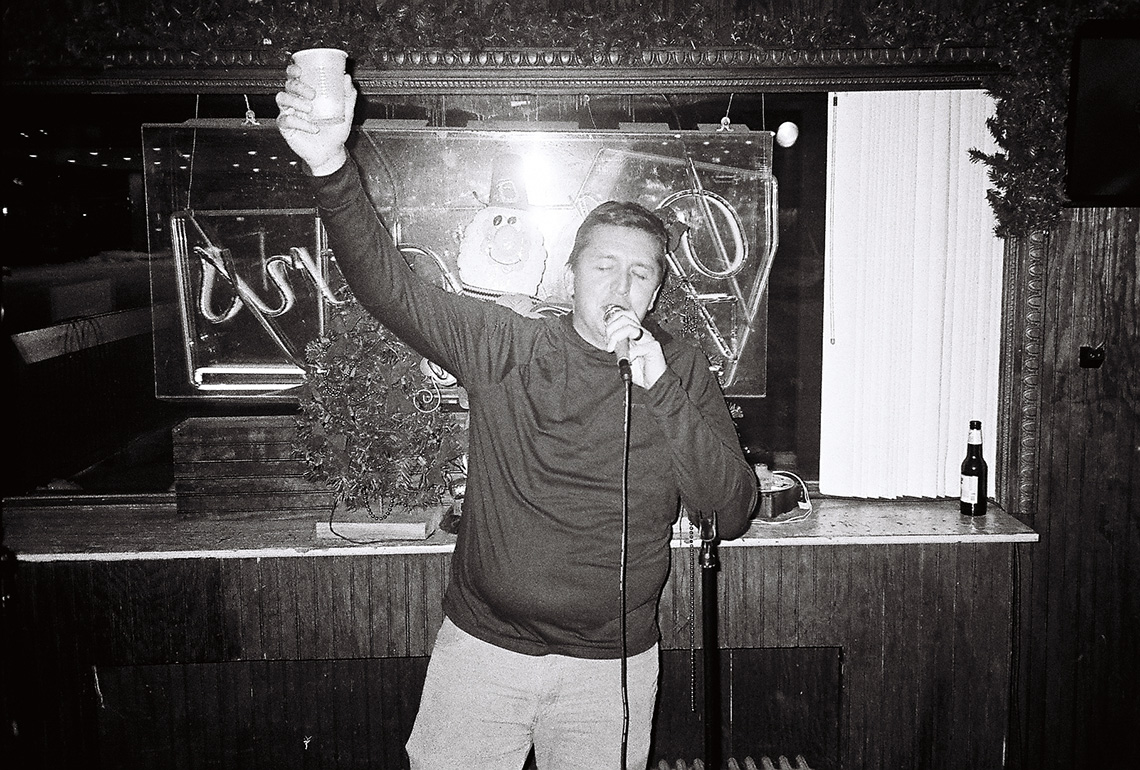

“Post-sauna barhopping in some favorite Marquette watering holes. Just before bar close, Robbie had the entire crowd at Flanigan’s singing along with ‘Take Me Home, Country Roads.’” Photo: Colin Clancy

“Marquette’s T-bar in all its glory. If we’d hit it on race league night, we could have danced to live bluegrass in unbuckled ski boots like old times.” Photo: Colin Clancy

As ninth graders this drive took forever, and we plugged a miniature TV into the cigarette lighter to occupy our time. Now, the two-and-a-half-hour trip north from Kalamazoo, MI, to Crystal Mountain doesn’t feel long enough to catch up with my childhood best friend, Geoff Lindenberg. His parents had a house that was walking distance from the lifts where we spent nearly every weekend during our high school winters and then for races with our college ski team. It’s 37 degrees and spitting rain as we pull into Crystal. The mountain itself looks the same as it did 15 years ago, but the base village is hardly recognizable. Hotels, hot tubs and restaurants line the streets. The ski hill where I spent so many weekends is now a full-on resort.

We hit the mountain in party mob fashion, traversing the entire hill and loading the lifts in different combinations with each run. Despite the mist, the snow feels nice under our skis—a bit wet, but firm enough to hold a deep carve. We lap a steep, wide burner at far skier’s right called Buck, a run I’d spent hours on in a past life, chasing sheer speed and skiing it slightly differently each time in search of the perfect line.

Rain corn harvest in full effect on an unseasonably soggy winter night at Crystal Mountain, MI. Photo: Colin Clancy

It’s fun to ski a place loaded with so many memories, but there’s something special about your home hill in pure skiing terms too. Somewhere deep down is the knowledge of precisely how to ski these particular and unique slopes for maximum enjoyment. Knowing every pitch, every contour, every undulation and gully offers the ability to ski it fully, finding the highest G-force of a carve and the little spots that can make your stomach drop. My friends and I ski these slopes as we’d done many times before, with nobody particularly leading and nobody falling behind, turning like a murmuration.

THE SCANDINAVIAN IMMIGRANTS WHO BROUGHT SKIING TO THE U.P. ALSO BROUGHT SOMETHING ANY TIRED SKIER CAN GET BEHIND: Saunas.

“The mountain here may be relatively modest in size, but Marquette, MI, is a ski town through and through, as evidenced by the ski fence outside Blackrocks Brewery. Photo: Colin Clancy

At lunchtime, Geoff mans the parking-lot grill while Robbie, Maggie Walters, Adam Watson, and Brad and Mara Russell sit in a semicircle of camp chairs swapping Crystal stories, like the one about the cops surrounding our college ski team party. We’d crammed three ski teams worth of people and kegs into the garage and, at the count of three, burst out like bats from hell, high-stepping through knee- deep snow into the woods, hiding behind skinny lodgepole pines. Years later, my heartbeat accelerates with the telling of the story.

Mara, a liquor distributor by trade, hands around a canned vodka concoction, dubbed “Mom Water.” I grab a blueberry-peach “Linda” and take a swig. The conversation changes to the nagging injuries of getting older. Of the seven of us, I count at least five bum knees, two bad backs, and lots of general soreness. For me it’s a persistent ankle injury that flared up to softball size a few weeks ago. I’m walking with a cane, and putting on a ski boot involves closing my eyes, biting my lip and jamming my foot down like I’m trying to stuff loose sausage into a casing.

above from top left to bottom

“There may have been more grass than you’d like to see in January, but after our first ski day was cancelled due to weather, we were just happy to find snow to slide on at Crystal Mountain, MI.” Photo: Colin Clancy

“We were the only group tailgating in an out-of-the-way Crystal parking lot, and it felt like the mountain belonged to us.” Photo: Colin Clancy

“Rain, fog and thin snow cover didn’t stop the crowds from enjoying one of Michigan’s best destination ski resorts, Crystal Mountain.” Photo: Colin Clancy

In 1905, skiers in Ishpheming, MI, formed the National Skiing Association, and the small Upper Peninsula town near Marquette is now home to the U.S. Ski and Snowboard Hall of Fame and Museum. Photo: Colin Clancy

After lunch, the rain picks up—the kind that soaks clear through Gore-Tex and stains hands with seepage from glove leather. Wet base layers make us shiver but don’t deter us. Maggie and Robbie poke head and arm holes in trash bags for a few runs, but it is too late for that; we are already sop- ping. The snow, though, remains surprisingly firm and fast, as if our wills for good skiing have overpowered the weather. Tomorrow, only Maggie, Robbie, Adam and myself will continue the journey north, so I try to savor every run with the full group.

Though I’ve never lived within 80 miles of here, I feel at home. I think it’s the blue-green Great Lakes water. Living out West now, I miss that water dearly.

“We may have been soaked at Crystal Mountain, but a little potent potable on the chairlift warmed us from the inside out.” Photo: Colin Clancy

Growing up watching Warren Miller movies and dreaming about big mountains out West, we trash talked Michigan skiing despite our love for it. As teenagers we didn’t think much about the ski history here. We didn’t think about the roots that took hold with the arrival of Scandinavian immigrants in the late 1800s. We didn’t consider that Michigan ski jumps were considered some of the best in the world in the early 20th century, nor that Michiganders set world records away from home. We didn’t consider that with over 40 ski areas still operating, Michigan is second only to New York in that regard.

No part of Michigan holds more ski culture and history than the Upper Peninsula. After a rainy first couple of days of our trip, we cross the Mackinac Bridge in search of that history and find something else—snow. After six harrowing hours on the road we pull into Marquette, where I lived for most of my 20s and where lake effect snow off Lake Superior had been pounding 500-vertical-foot Marquette Mountain all day.

Trash-bag skiing may not be the most glamorous affair, but sometimes the means are worth the ends. Suiting up for the deluge at Crystal Mountain, MI. Photo: Colin Clancy

In low-20-degree temps, we rip groomers and play in the glades. Robbie, having ditched his teles for alpine skis, pops off side hits, and Adam follows his train. When the after-school crowd shows up, we go into singles line mode, meeting at the top of each run.

As the daylight wanes, the lights power up. Something about night skiing feels like skiing in its purest form, maybe because as kids we spent 90 percent of our time on the slopes after dark. Under the lights, the snow falls so hard that the chairlift’s haul rope vanishes into a curtain of white. My legs feel strong and dialed, my ankle pain-free for the first time in weeks. The temp has dropped a few degrees, and the snow firms into a perfect, edge-holding softpack. Hero stuff. In a favorite term of ski hill snow reports, we’d call this “packed powder.” We bomb it in fast, wide and low carves. I follow the others and take in the view.

“A free-refills kind of night at Marquette Mountain and the best skiing of the trip. On the south shore of the big lake, nights like this are common.” Photo: Colin Clancy

It’s possible that Maggie’s carves are the prettiest I’ve ever seen, powerful but graceful—almost like a racer but a bit more laid back and flowy. She talks about learning to ski in her dad’s tracks at Sugarloaf, a hill near Traverse City, MI, that’s now closed. “Literally in his tracks,” she says. “I don’t know how he ever saw me ski enough to give me pointers because I was always behind him.” He’s since passed on, but Maggie’s skiing, and those turns, continue to be part of his legacy.

The Scandinavian immigrants who brought skiing to the U.P. also brought something any tired skier can get behind: saunas. After our ski boots come off that evening we follow a local buddy, Matt Torreano, along a snowy path to the back of his house where he’d lit the sauna stove that afternoon.

Welcome to the Marquette snow globe, courtesy of the Great Lakes’ unique winter weather patterns. Photo: Colin Clancy

“Help yourself to anything in the fridge,” he says, pointing at a stack of Hamm’s sitting in the snow on a little shelf outside the sauna window.

Inside, the thick 170-degree air has the dense smell of wet cedar. I breathe deep and slow, feeling the sweat start to roll. Torreano douses the sauna rocks and the air thickens. I inhale deeply. The world feels good. Just when I think I can’t stand the heat anymore, Adam makes a mad dash outside and flops into the snow, giggling. We all follow, a wonderful shock.

We haul through the top of Middle Earth before contemplating whether the dense trees of Gandalf or Frodo offer the best lines. One of the things I love most about tree skiing is the choose-your-own-adventure nature of it.

“The target event at the 136th annual ski jump on Suicide Hill put on by Ishpeming Ski Club. Ski jumping has been a tradition in the Upper Peninsula since the late 1800s. Originally brought here by Norwegian immigrants, the tradition stands today. In the target event skiers try to land as close as possible to the target painted in the landing zone.” Photo: Kyle Bolen

Steam rises from a placid Lake Superior, the car thermometer reading a balmy 9 degrees as we enter the Keweenaw Peninsula. The 150-mile thumb’s up jutting from the western U.P. into Lake Superior is a magnet for lake effect snow, and it can get pummeled nightly for a month straight. Average January snowfall up here tops 70 inches but can exceed 100, so we are disappointed to learn that last night’s storm down south didn’t drop a single flake locally.

Near the tip of the Keweenaw, and mainland Michigan’s northernmost point, Mount Bohemia stretches into a bluebird sky. This U.P. classic looks like a real mountain in a way that’s atypical for Michigan. It’s steep and rugged, with 900 feet of ungroomed vertical. I’d been here once, over a decade ago, when the base area consisted of just a couple of yurts. Now it offers a whole hobbit shire of them, plus a bunch of tiny log cabins, a hostel and the largest hot tub in the U.P.

Night moves come with some serious payoffs. Scoring big on a sleeper night in Marquette, MI. Photo: Colin Clancy

We load one of two fixed-grip chairs painted an oddball lime green and purple. Even though it was built for three riders, a sign at the base instructs us to “load as a double.”

Halfway up I look over my shoulder and the view hits me. Seemingly right at the base, a frozen Lac La Belle is untouched save for a lone snowmobile track. Beyond that a thin strip of pine forest is the only thing between us and Lake Superior on the horizon. Though I’ve never lived within 80 miles of here, I feel at home. I think it’s the blue-green Great Lakes water. Living out West now, I miss that water dearly.

“A snow-swept U.S. Route 2—with its tourist traps, pasty shops and gas stations selling smoked whitefish—welcomes us to the Upper Peninsula.” Photo: Colin Clancy

Robbie’s a Bohemia veteran, catching the annual $100 season pass sale that happens one day only each December, and making the 600-mile trek from Kalamazoo at least once or twice per winter. This place offers tree skiing at its finest, and since Robbie knows the area, we follow him across thin snow cover, finding smooth lines through the trees with slivers of Superior in the distance.

The runs at Bohemia are named after planets and Lord of the Rings characters. There are thickly treed, steep, jump-turn-only sections, and rockstar runs spaced wide enough for speed. We haul through the top of Middle Earth before contemplating whether the dense trees of Gandalf or Frodo offer the best lines. One of the things I love most about tree skiing is the choose-your-own-adventure nature of it. In trees like Bohemia’s, you’ll never ski the same line twice. The density of trees makes these 585 acres ski like a much bigger resort.

“I ran into Jackson Pundt (pictured) while the two of us were ski touring on the property of Mont Ripley, a university-owned ski operation in Ripley, MI. Mont Ripley doesn’t spin lifts until 3 p.m. on weekdays, allegedly so Michigan Tech students don’t skip class on powder days. If you are willing to get up at the crack of noon, you have hours to ski fresh turns before the area opens. The hill overlooks the towns of Houghton and Hancock, only separated by a lift bridge. But be careful if you are skipping class—your professor is able to see you on the slopes from campus.” Photo: Kyle Bolen

Just when it seems that we might be hopelessly lost, we pop out onto a road. We take off our skis, sit down in the snow and wait for the bus to take us back to the lift—just one feature of a mountain built to ski anywhere you please. The wait for the shuttle is a welcome respite for hurting bodies. We talk about how it’d be nice to ski a groomer. Then again, groomers don’t exist here. By the end of the day, when golden hour light casts long shadows from these hundreds of thousands of pines, we are all absolutely beat.

We roll out our sleeping bags on bunks in the log cabin hostel and hit the giant hot tub. Though there are probably 20 people, it doesn’t feel cramped. Bohemia may be more developed than it was last time I skied here, but the vibe is the same—more backwoods hippie commune than resort, its crowd a mix of fiercely loyal regulars and first-timers making the bucket-list pilgrimage.

“I awoke on a frigid February morning in a Depression-era cabin built by the Civilian Conservation Corps and run by the Keweenaw Mountain Lodge. This was during a spell of days well below zero degrees. We were dressing for a storm-skiing day at Mount Bohemia while wondering how many layers of down we’d brought. Every windowpane was covered in beautiful frosty designs that hinted at the temperatures they restrained.” Photo: Kyle Bolen

I towel off to FaceTime my 2-year-old son, Jackson, before his bedtime and tell him just two more sleeps until I’d see him. “You ski fast, dada?” he asks. “Yeah, bud,” I say. “I ski fast.”

After my call, I find the crew saddled up to the log cabin bar talking with Missy, the bartender who lived in an unheated trailer in the parking lot for years before buying a house near the mountain. On the bar top she drapes a trail map handkerchief over a rocks glass, simulating the contour of the mountain, and points out a dozen different spots we should ski tomorrow. It’s going to be another good day.

Missy takes a tray of drinks to the hot tub. Everybody knows her by name. They reach out from the water to give sopping wet hugs as hot tub steam billows into the night.