Rewind

Skiboarding: A Eulogy

Remembering the shortest link in skiing's evolutionary chain

In a spread eagle world, Mike Nick was throwing 720s.

Nick had just topped the Winter X Games podium for the debut of skiboard slopestyle, and it was clear to everybody watching the event on TV: this sport was unlike anything ever seen before. The year was 1998, and skiboarding was the future.

Of course, that future never came to fruition. Skiboarding would enjoy two more seasons as part of the X Games, and while ESPN’s decision to discontinue the event in 2001 may not have been the nail in the sport’s coffin, it certainly was a bellwether.

“It’s always thought of as this blown-off bastard child of skiing that doesn’t get any credit,” says Nick, who went on to have plenty of X Games success on long skis. “It was this subculture of skiing, and yet skiing didn’t really give it any respect. It’s written off by skiers as not having an impact, but it totally did—whether they admit it or not.”

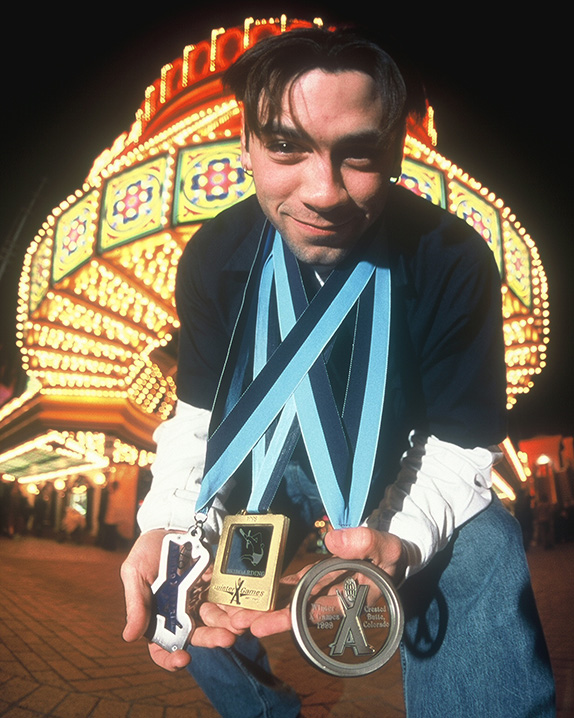

ABOVE Mike Nick and Jay Levinthal stood atop the skiboarding world in 1998, when they took first and third at the X Games, respectively. Photo: Mike Nick Archive

While the arc of skiboarding may have been short-lived, its impact on the trajectory of the sport is hard to ignore. In a time when terrain parks were still known as “snowboard parks,” skiboards offered the first taste of what was to become newschool skiing. The boards themselves were incredibly maneuverable, especially compared to the 200cm straight skis that were still the norm in those days. The ski world was still getting used to terms like “parabolic” and “shaped ski,” and had just heard whispers of “twin tip.” People were realizing that shorter skis equaled easier turns and spins, so it only seemed natural to take that knowledge all the way to its extreme.

“You’ve got to put your head back in time, and at that time nothing was exciting or innovative about skiing,” says Jason Levinthal, who founded Line Skis in 1995 after experimenting with very short, twin tip ski designs in his parents’ garage in Albany, NY. “Snowboarding was blowing up, and it was 100 times more exciting than skiing. You could do everything on a snowboard: you could carve, you could go backwards, you could do tricks. None of that was possible on skis, really.”

Levinthal and friends like Nick skied and snowboarded, but wanted to pull off the same kind of progressive tricks on skis that they were landing on boards. “Skis were all the same,” he says. “You couldn’t do much on them—you could do a spread eagle, maybe a 360, ski some bumps. With skiboards, we were trying to rejuvenate the sport. It was dying, honestly.” He adds that anyone under 20 was ditching skiing for snowboarding’s infinite upside.

“We didn’t have to do much to make skiing enticing and cool again at that point in time, because there was nothing cool about it,” says Levinthal.

Austrian brand, Kneissl, launched the Bigfoot in 1991 and brands like Line started building very short and wide, twin tip skis and calling them skiboards as early as 1995. But, it wasn’t until Salomon introduced Snowblades in 1998 that skiboarding really hit the mainstream. That was also the year that skiboarding slopestyle began its three-year run as an X Games event.

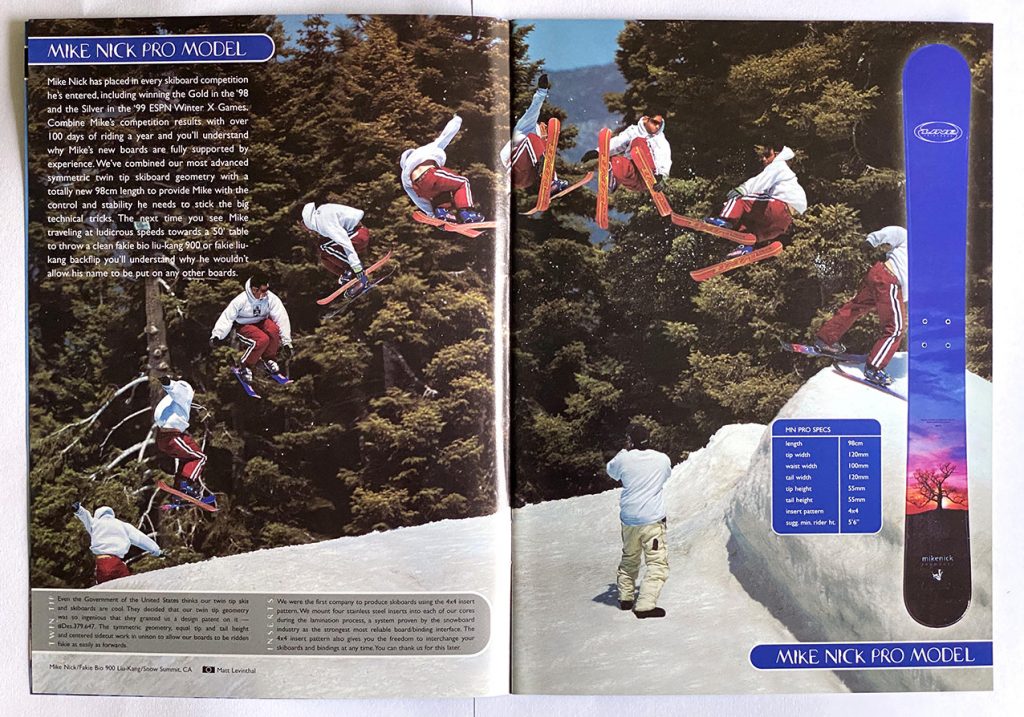

ABOVE The Mike Nick Pro Model occupied space in Line’s annual ski catalog, but skiboarding also graced the pages of FREEZE, POWDER, and The New York Times Magazine in its heyday. Photo: Jay Levinthal Archive

During that 1998-1999 season, skiboarding boomed. Skiboard sales in the US reached $11.4 million that season, a jump of over 2,000 percent from the $466,000 of the previous year. At skiboarding’s peak, about 25 brands manufactured skiboards, including many of the major ski brands. In Skiing magazine’s December 1999 gear guide, skiboards like the Line Mike Nick Pro Model, the Canon M7, the Dynastar Twin Alphabet, the Elan TRX Rollerski, and the K2 Fatty, occupied prime real estate.

“Skiboarding ignited a revolution in skiing,” Levinthal says. “It allowed us to think way outside the box of what a ski is and what you can do on skis, period. All the tricks that came from that period were night and day to anything that had ever been done.” Snowboarding-inspired tricks involving grabs and landing backwards started to take off in the ski world. Thanks to skiboarding, skiing had started to close the gap between the two competing snow disciplines.

But just as skiboarding started to legitimize itself as a full-on category unto itself, the sport’s glory began to fizzle. Skiboards may have been agile in the park and fun for party shredding with friends, but they were squirrely at speed, sunk like the Titanic in powder, and led to bruised tailbones for anybody accustomed to landing a little backset. Many of the sport’s best athletes began to realize that the now commonplace mid-fat twin tip skis like the Salomon 1080 provided more stability and more landing surface, without sacrificing much maneuverability.

Without a skiboarding event in its 2001 lineup, the X Games invited Nick to its ski events as a consolation prize. “Maybe they just felt bad,” he says. “This guy’s gotten on the podium three years in a row. Let’s just give him a kick at the can on skis.”

Nick went to Mammoth for a week before the 2001 X Games to relearn all of his tricks. “I’ll never forget the first time I went to hit a jump on long skis and throw a Cab 5. I set my rotation way too early and literally whacked the tips of my skis on the jump.”

When he showed up at the X Games he couldn’t shake the feeling that some skiers didn’t want him there. “There was some animosity toward me because I got this free invite,” he says. “Maybe they thought I didn’t deserve it. Most skiers had respect for what we’d done on skiboards, but then there were a bunch of guys that talked constantly.” Nick topped the leaderboard for two of the three runs of that year’s Big Air event—the only skier to throw three different tricks. He ended up placing fifth, with many people feeling he’d been robbed.

above left to right (click to enlarge)

Nick shows off his hardware during the three year run of skiboarding at Winter X. Photo: Mike Nick Archives

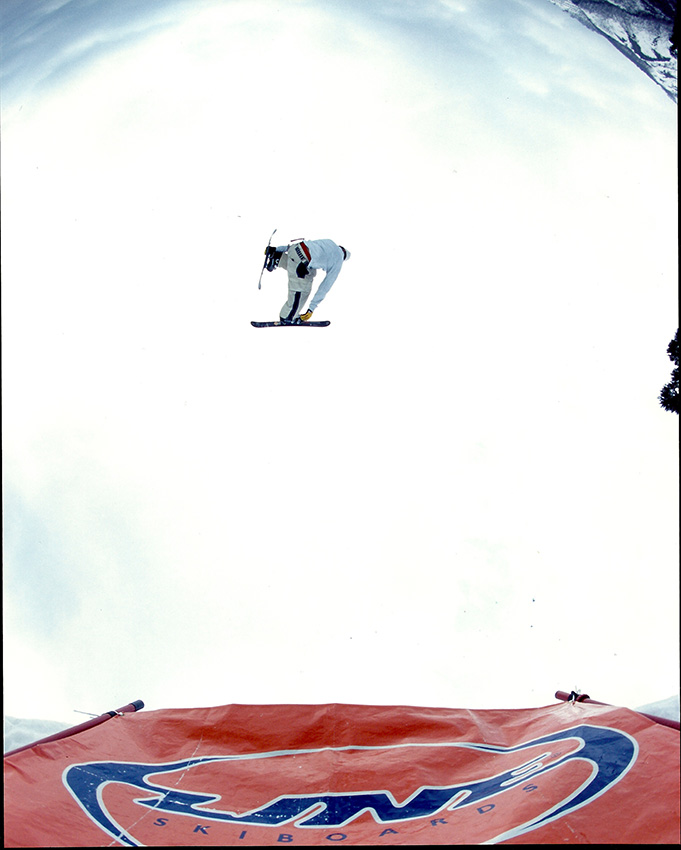

For the first time, skiboarding unlocked halfpipes, quarterpipes and other terrain features once only thought to be part of the snowboarding world. Nick flashing some style for the cameras. Photo: Mike Nick Archives

“I never really thought of it as skiboarding meeting its end,” Levinthal says. “I just thought of it as continuing to evolve into what skis are today. Salomon came out with the Snowblade because they saw the skis that we were making, and the Snowblade inspired the 1080, which inspired myself making longer versions as well.” In turn, those skis quickly inspired fatter and wider skis.

“To me it was like lighting a fire. you have to get a spark started. Yeah, they were short, but they’re a hell of a lot closer to today’s skis than anything that was made at the time,” he says.

Skiboarding looks goofy when we look back on it now. Find any of the old videos on YouTube, and there will be moments as cringe-worthy as bleached tips and puka shell necklaces. But even today, modern skiers like Phil Casabon and Henrik Harlaut acknowledge the influence skiboarding has had on their skiing styles, having studied films of their predecessors like Nick. Casabon says those early skiboarders showed the possibilities of stylish skiing without poles, a modus operandi that the Canadian adopted during his rise into the upper echelon of street skiing.

“You can look at skiboards compared to today’s skis and say, ‘Haha, those are lame,’” Levinthal says. “And you could look at a Ford model T and say, ‘That’s lame. Look, they had wood rims. How silly.’ But before that, all they had was horses. It was just the most radical departure.” Levinthal was developing skiboards for the same customer that was riding a snowboard, a skateboard, and a BMX bike. He says he was designing products people that wanted skiing to be more than just about racing and moguls.

Current devotees keep a few dedicated skiboard brands like RVL8 afloat. And while you’re unlikely to see it on the front cover of any marketing materials, K2 still produces its Fatty. Scouring the bowels of the internet for skiboarding’s obituary, one comes up empty handed. Instead, active forums of loyal followers prove that skiboarding is, indeed, alive.

ABOVE Nick sessioning the summer park at Mount Hood, an area once only open to snowboarders. Photo: Jay Levinthal Archive

“We’re not saving lives, we’re having fun,” explains Jason Roussel in an article on skiboardmagazine.com from 2016. “We have an inexplicable love for the feeling of sliding around on snow with two short planks strapped to our feet.”

Those like Levinthal understand that on the evolutionary diagram, skiboarding falls somewhere between ape and man, with a select few still out there riding them passionately in the wild. But who knows, maybe 20 years down the road we’ll look at the ultra-wide, ultra-rockered skis of today and ask ‘What were we even thinking?’ We might all of us be Neanderthals, yet.